The area is flat, no hill higher than five meters - unlike the steep mountains in the hinterland.

Off the top of your head, you wouldn't think that this scenery is under threat. But: "The delta has another twenty years to live, that's it." That's what activist Jordi Parés says, adding: "Unless something is done about it."

Parés, from the presidency of the Associació Sediments, sees his homeland under threat from three sides: "The delta is sinking due to settlement and agriculture. Added to this is the rising sea level due to climate change. But the biggest threat is the lack of sediment."

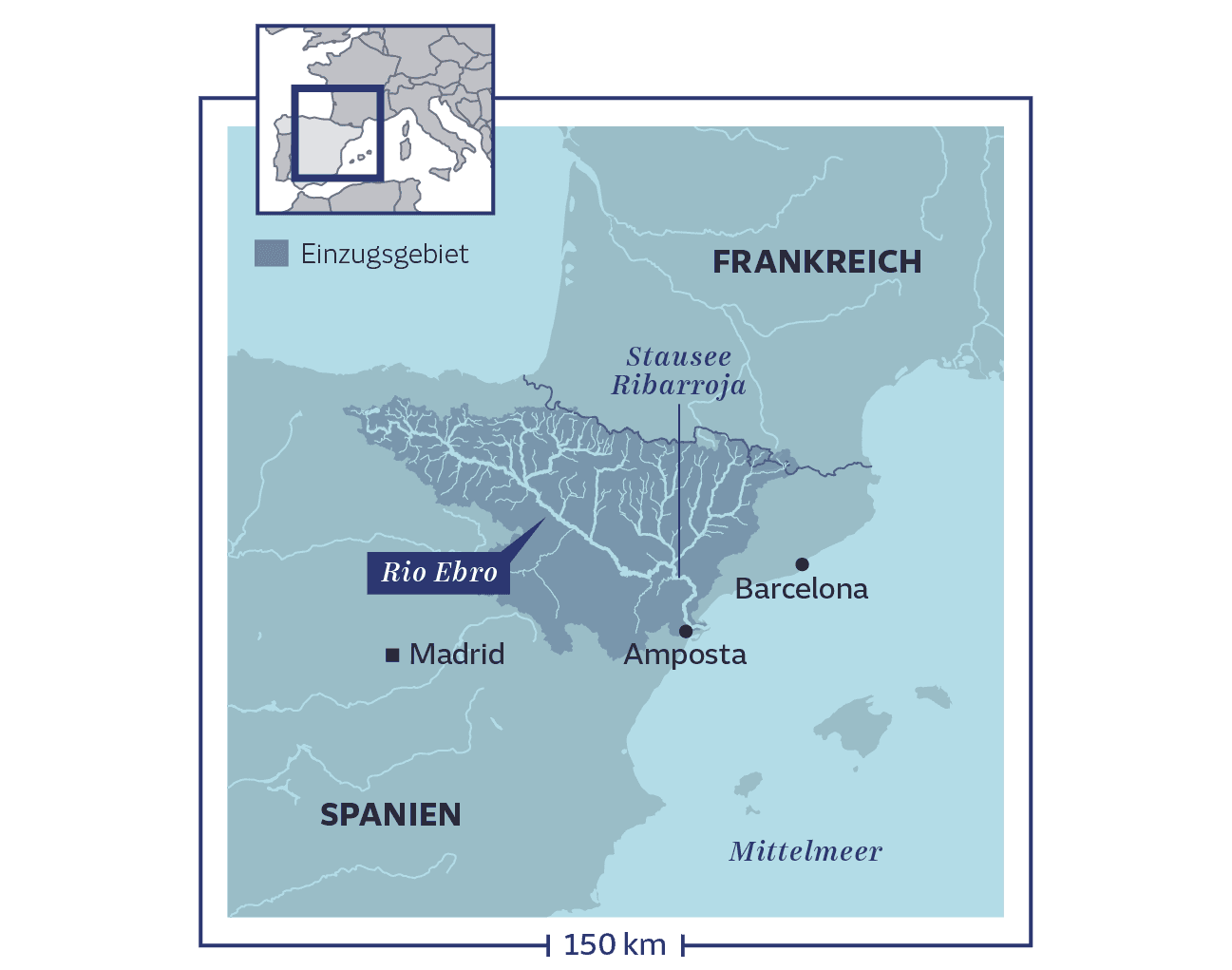

A few hundred meters from Parés' quiet family home, the Ebro slowly meanders towards its end. Its fresh water, distributed via canals, is the elixir of life for the arroceros, the local rice farmers. The delta contributes a fifth of Spain's rice production, around 135,000 tons a year.

But this elixir lacks one essential ingredient: sediment. Fresh sand, soil and nutrients do not reach the rice plantations or the tip of the delta. More than three hundred bird species live there in a nature reserve, including flamingos and the golden-crowned night heron in one of its last habitats in Western Europe.

But the delta is visibly losing land and height. Jordi Parés urges us to hurry: "We have to change! Otherwise our descendants will be the first climate refugees in Europe!" Once the delta has disappeared, the birds will also lose their habitat.

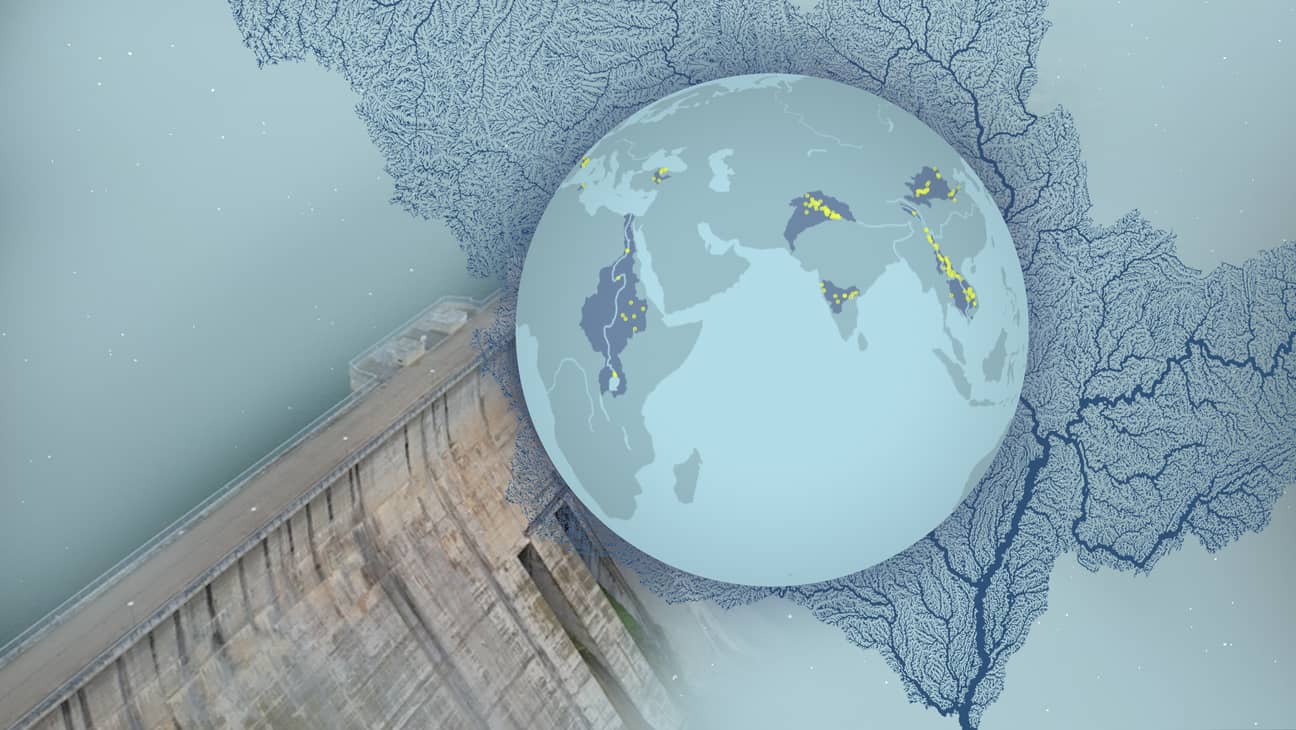

The disaster began when the first dams were built upstream - to supply electricity, but also to store drinking water. Before that, 20 million tons of soil had reached the coast. At present, only 1.4 million tons remain - with the result that the delta has shrunk by a good five square kilometers over the past 40 years, according to research by the SZ. Satellite images show how much the coast has changed since then.

Farmers, scientists, conservationists and tourists can all agree that something needs to be done about this. But this unity is already breaking down. If you ask the arroceros, who sometimes work their plots with hoes and spades, sometimes with tractors, they describe the situation unanimously.

What can be done about it? Some argue in favor of dykes for protection.

The activist Parés is indignant: "If they could, there would be dykes everywhere. Huge dykes, twenty meters high! A gigantic wall against nature. But they are condemning the delta." According to Parés, dykes have not worked in the past, they have been undermined.

His association, on the other hand, relies on natural barriers. "We need more beach and fewer rice fields to absorb the energy of the sea. And that of the storms - like Gloria." Winter storm Gloria, which is believed to have been exacerbated by climate change, marked a turning point at the beginning of 2020. Never before had such heavy rainfall been recorded in the region, the waves on the Mediterranean reached heights of up to thirteen meters and their foothills flooded the entire estuary. The region lost the illusion that everything was fine - and large areas to the sea.

The Ebro is being researched here in Amposta at the Eurecat Technology Institute. "The delta has lost around four kilometers in length in the last eighty years," says Carles Ibañez, Scientific Director of the Climate Resilience Centre at Eurecat.

This is why the delta can no longer avoid dykes for the time being, at least where there is no (longer) a natural beach. However, this only combats erosion. More sediment will therefore not reach the delta. If you want to save the delta, you have to start with the dams.

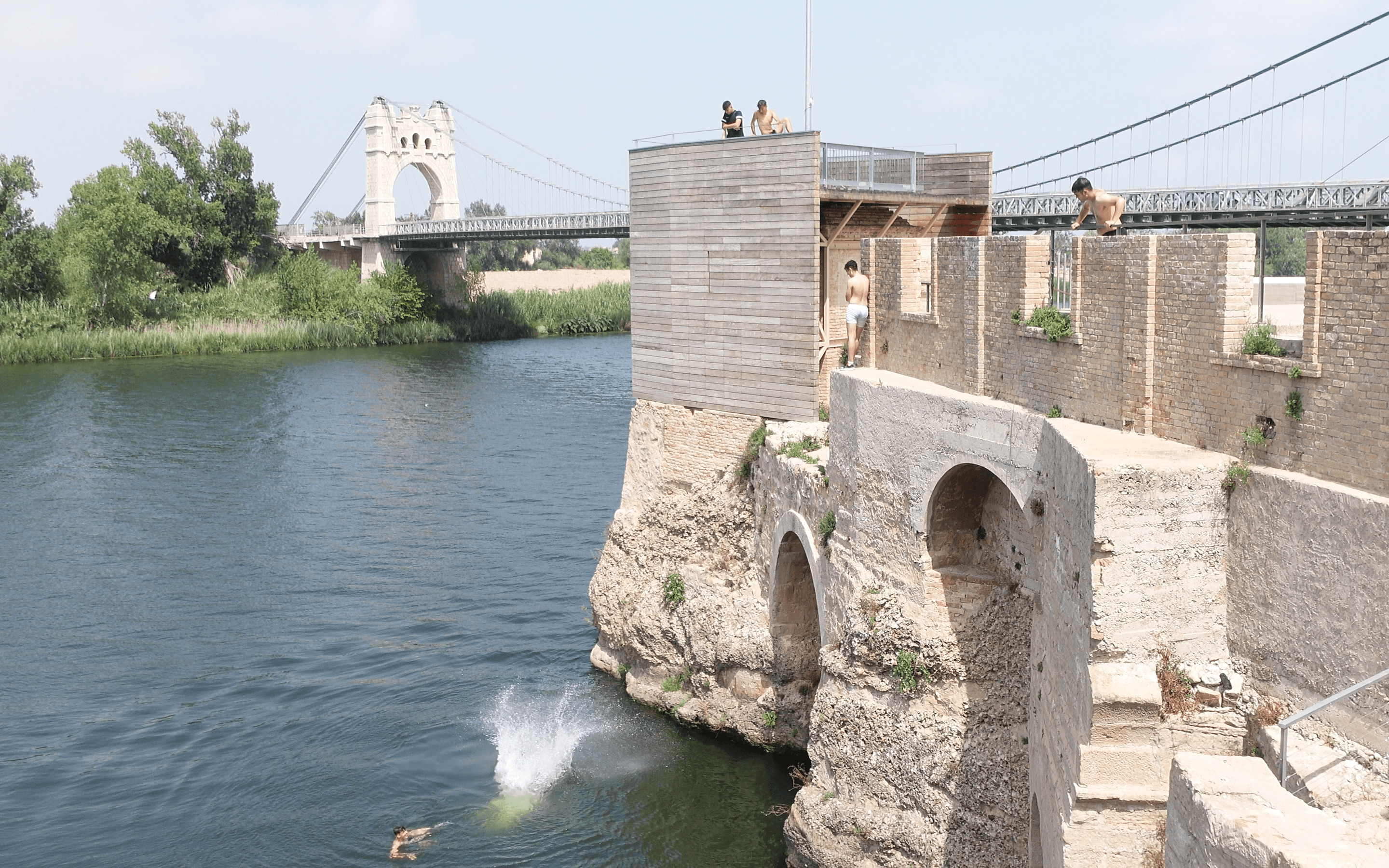

Their effect is already noticeable shortly upstream of Amposta. The Ebro is no longer flowing. It stands still.

The village of Mequinenza lies slightly downstream. The new village of Mequinenza, it should be added. Because the old one was flooded by the Ribarroja reservoir in 1969 and the inhabitants relocated. Unexpectedly, it developed into a European competitive sports center for canoeing, kayaking and rowing. National teams appreciate the natural channel formed by the lake and training in pleasant temperatures. But the water sports paradise only lasted a while.

Mariá Teresa Godia has lived here for a long time and is a sports rowing coach at the local club.

"Last week, they had to lower the Ribarroja reservoir by one meter," says coach Godia. Before that, it hadn't rained for a long time and planned races had to be canceled. "We only had a draught of one meter and could no longer sail because boats and oars get stuck in the mud."

Godia identifies another reservoir called Barasona on a tributary of the Ebro on the edge of the Pyrenees as the cause. This has a deep drainage gate that can be used to flush out sediment.

This was not done for decades, probably for repair and cost reasons, says Carles Ibañez, until the gates themselves became blocked. The sediments became rock-hard and the lake almost unusable. Only with great effort was it possible to loosen the soil and open the gates in 1995. "These tons of sediment ended up here," says Godia.

"Fifty years ago the dam, for thirty years the mud! All this without anyone taking responsibility. It's time for someone to make up for what Mequinenza has suffered with all this," says Godia.

But who? And how?

The Ribarroja reservoir is operated by Endesa.

This is because sedimentation occurs at the head of the reservoirs and not at the dams. The Hydrographic Confederation of the Ebro, an authority of the Spanish government in Zaragoza, is legally responsible.

They are indeed busy there. Miguel Garcia Ángel Vera, Head of Water Planning, takes a lot of time to demonstrate this. He has four hydrological plans for the Ebro, thousands of pages of documents and a new six-year plan to combat sedimentation. 18.4 million euros have been approved for this. "A lot of money," says Vera. 7.5 million euros alone are earmarked to combat erosion in the delta. The rest is for getting the sediment back into the delta.

The question is why the public sector should pay for this damage. "A concession for hydropower rights also gives companies obligations. However, in the case of Endesa, the issue of sediment was not addressed at the time," says Vera. Now they would do things differently. "But the current concession doesn't expire until 2060." Without countermeasures, however, the delta would disappear by then and large parts of the lakes would silt up.

His authority is well aware of the challenges: instead of the current 1.4 million tons of sediment per year, twice that amount would have to reach the Ebro Delta to counteract the worst damage caused by erosion. And ten times that amount for the delta to grow minimally, i.e. to behave almost naturally.

According to a report, many solutions, such as channeling the sediment past the dams, are "unfeasible", for example continuous dredging and forwarding of the sediment. For Ribarroja alone, 75 to 150 kilometers of canal pipes would be necessary. "Opening the lower gates is also difficult due to the lack of a gradient in the lake," says Vera.

The mud is also extremely tough, says Vera. "I have walked through this sediment. On days when the water is low, you can. It's not loose sand, it's sticky like plasticine. You get stuck in it when you step in it." Moving this material is difficult.

Back downstream, in Amposta, researcher Ibañez has been working on solutions for a long time: "We have developed a system that pumps sediment out of the lake and transports it past the dam via floating pipes. And it's all very cost-effective," says Ibañez. Under pressure, three to four million tons of sediment are to be moved each year. Cost: ten million euros for the purchase, five million for the operation per year.

However, his proposal has not yet been accepted. But why? "To be honest, I don't understand it either," says Ibañez. The sustainability researcher sounds disillusioned. "The biggest obstacle to saving the delta is the inertia of politicians and administrators." Progressive erosion and climate change are forcing action. "The longer we take, the more expensive and complex the solution will be."