Wheeling and Dealing

The opening of the new museum, built at a cost of almost 13 million euros, was a major event in the tiny village of Alkersum on Germany’s North Sea island of Föhr. The celebration even attracted two queens – Sangay Choden Wangchuk of Bhutan and Margrethe II of Denmark. The guests also included ambassadors from several countries and celebrities like German newspaper publisher Friede Springer in addition to entrepreneurs and politicians. Bubbly was poured and music played. It was almost as if, for one day on July 31, 2009, no-nonsense Föhr had swapped places with its more glamorous, neighboring island, Sylt.

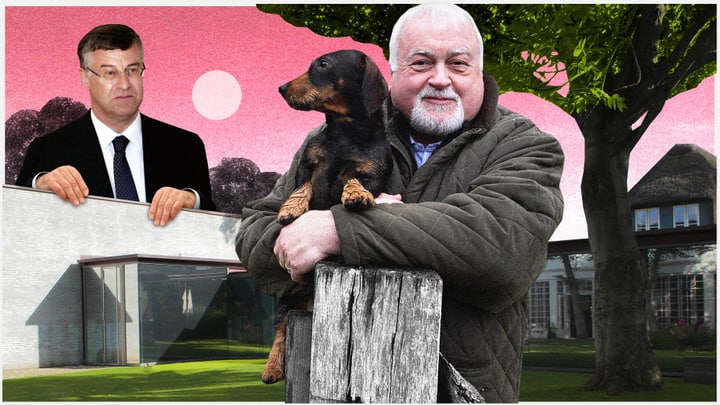

Since its opening, the Museum Kunst der Westküste (Museum of West Coast Art) has hosted temporary exhibitions showing works by Max Liebermann, Edvard Munch or Max Beckmann, with a focus on northern European art from the 19th and early 20th centuries. All the works originate from the collection of Swedish pharmaceuticals magnate Frederik Paulsen, who also counted among the guests at the museum’s grand opening eight years ago. The Swedish billionaire with North Frisian ancestry, who now lives in Lausanne, Switzerland, donated the entire museum to the island of his ancestors. “You are a business personality who has a sense for his societal responsibility and also acts on it,” an enthusiastic Peter Harry Carstensen, then-governor of the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, said of the patron at the time.

Carstensen resigned from his position three years later, but he still visits the museum. For business reasons, if you will.

After all, Carstensen, who has since retired from politics, is listed in the Netherlands’ business registry as one of three directors of Peloponnesus B.V., a company registered in the Dutch city of Hoofddorp. According to its annual report, the Dutch company handles the “upkeep and dissemination of art as well as the operation of the Museum Kunst der Westküste on Föhr.” Peloponnesus is part of a broad network of companies that are part of the Paulsen corporation. A memo in the Paradise Papers served as the impetus for the reporting on this story. When contacted for a response by the Süddeutsche Zeitung and German public broadcaster NDR, one of the reporting partners on this project, a lawyer for Paulsen wrote that the company structure had been chosen to “ensure the greatest possible flexibility in the lending of artworks and the respective collections.”

The firm Ferring Pharmaceuticals was founded in 1950 by Paulsen’s father, who had fled to Malmö, Sweden, to escape the Nazis in Dagebüll in Frisia. His son Frederik Paulsen, today 67 years old, has largely withdrawn from the company’s activities. He now travels around the world as an explorer, researcher and philanthropist, with a penchant for unique places. In Bhutan, for example, he has supported the art of rug-weaving with large donations, hence his acquaintance with the country’s royal family. He operates a winery in Georgia, is building fertility clinics in Russia and he has been to the North Pole multiple times.

In North Frisia, the home of his ancestors, Frederik continues to support all forms of Frisian culture – including the Frisian language in schools, historical archives and even a Frisian radio station through the Ferring Foundation, an organization established by his father. He also donates to the conserative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party. At least 450,000 euros flowed from Paulsen’s company Ferring into the CDU’s coffers between 2003 and 2009. Paulsen himself appears as a donor three times in the database, with a total of 118,000 euros between 2002 and 2010. From June 2002 to September 2010, Peter Harry Carstensen served as head of the CDU's state chapter. After that, no more large donations are registered for Paulsen or Ferring.

A Frisian through and through, Carstensen is a fan of the homeland loyalty shown by the Paulsen family. Responding to questions submitted by the Süddeutsche Zeitung and NDR, 70-year-old Carstensen wrote in a statement that he was "extraordinarily thankful" for "the Paulsen family’s years of dedication." Back when he was a member of the German parliament, the Bundestag, Carstensen's electoral district was Northern Frisia, where most of the foundation’s work is done.

If Carstensen were a volunteer in his capacity at Paulsen’s museum on Föhr, one would assume he was providing his Frisian expertise out of sheer gratitude for all of Paulsen’s efforts in the area; he means a lot to both Carstensen and Frisia. As it happens, however, the pharma-billionaire also made the former politician a part of his company network – a capacity in which Carstensen also appears to draw money. According to the balance sheet for Peloponnesus B.V., which is part of the public record, the three "managing directors," one of whom is Carstensen, received a total of 90,000 euros in 2014. In 2015, the total was 45,000 euros. No figures were included for the other years. Paulsen himself is also listed as one of the directors.

The former Schleswig-Holstein governor didn’t dispute the events in question, but he also didn’t provide any sums. "In terms of the income I obtain from my activities, I obviously declare these fully and without exception to my tax office," he wrote. Carstensen also wrote that there are generally no secrets about the work he does and that "there are surely also references and information about many of them on the internet."

That may apply to his activities on behalf of the Gregor Mendel Foundation, an organization involved in plant breeding and of which Carstensen is a member of the board of trustees. It also applies to his supervisory board role at Chateau Mukhrani, the Paulsen winery in Georgia. When it comes to the director posting on the island of Föhr, however, there is no indication anywhere – neither "on the internet," nor in press archives nor on the museum’s own website. To establish that tie, you must do a targeted search in the Dutch business registry. Yet regarding his function in Föhr, Carsten wrote: "I reject the assessment that I did ‘not make this public’ as incorrect."

The documents indicate that Carstensen accepted the post just six months after he resigned as governor in 2012. He describes himself as a "non-executive director" of the museum with an advisory function. Carstensen explained that his involvement was a result of his "personal interest in this facility and the project’s extraordinarily positive effect on my home region." For his part, Paulsen conveyed that for him, Carstensen is "an esteemed point of contact for the preservation and promotion of Frisian culture."

So, was it all just a service provided to the community by two friends and nothing more? Timo Lange of the German anti-corruption organization LobbyControl has an altogether different take. "That is indeed a very interesting case," he said. "For exactly such situations, there is now a waiting period rule (in Schleswig-Holstein)." Following an initiative introduced by the state’s Pirate Party, politicians in Schleswig-Holstein making the shift into the private sector are required to appear before an ethical review commission that seeks to recognize potential conflicts of interests and then issues recommendations to the state government, which can impose a waiting period of up to two years. The trigger for the revolving-door initiative was the 2014 resignation of Andreas Breitner, of the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD), from his position as state interior minister to become the head of an association of housing management companies.

Whenever politicians make the shift to the private sector – regardless if it is former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who made the move to the Russian energy sector, former Chancellery Chief of Staff Ronald Pofalla, who took a job at national railway Deutsche Bahn, ex-Health Minister Daniel Bahr, who went to insurance giant Allianz, or former member of parliament Eckart von Klaeden, who shifted to Daimler – the same debate always arises: What are politicians allowed to do following their political career, and at what point are they allowed to do so? For members of the federal government in Berlin, revolving-door rules have been in place since 2015, but it has in no way become the standard for the German states.

LobbyControl expert Lange says that Carstensen’s ties to Paulsen represent exactly the kind of case that would be subject to Schleswig-Holstein’s waiting period rules. "If you don’t approach cases like that with maximum transparency, the impression could arise that political favors were being paid back. It could lead one to ask: What kind of deal was cut there?" Especially given that a lot of money had already flowed between the pharmaceutical magnate's company and the governor’s political party in the form of donations. "Political responsibility doesn’t end with political activity," says Timo Lange. The impression must be avoided that a politician is possibly providing lobby work for his new employer because he or she still has good contacts with politicians.

Paulsen rejects any suspicion that he is granting Carstensen any kind of "remuneration for political favors." The businessman stresses that he, "as a Swedish citizen and as a businessman and patron, obeys the law unconditionally and would never choose or support a structure or construct for his activities that is not legal."

Peter Harry Carstensen’s tone is similarly definitive. He says he sees absolutely no reason for his "activities or details about them to be disseminated widely or through the media." Nor does he provide any information about possible income from his role on the supervisory board of Paulsen’s winery in Georgia. Carstensen, who once served as agricultural policy expert for the CDU in its party caucus in the national parliament, says only that he serves in an advisory capacity at the winery because of his "expertise on agricultural issues."