Supplying Trucks to a Murderous Military

The military leaders of Myanmar are deploying widespread violence to crush peaceful demonstrations in the country. The soldiers are frequently deployed with the help of trucks built by a Chinese company – a large stake in which is held by a German company with a rich tradition. It is a story of ethics and responsibility in global trade.

And those letters lead us to the dark side of global trade and to sensitive questions of profit and ethics. Because from Sinotruk, there is a direct connection to Germany.

This story begins just a few days after Angel's death. Through an intermediary, a man got in touch with the Süddeutsche Zeitung, saying he had collected information regarding the brutal operations performed by the army in Myanmar, to which companies in Germany are linked. Specifically, the information points to a trail to the state of Bavaria – or, more specifically, to Munich.

The man calls himself Padauk, a variety of tree found in Myanmar. He asks that his real name or location not be published, but he is happy to identify the group he works with. It’s called Justice for Myanmar, a group of activists that collects evidence of corruption and abuse of power in the Myanmar military. Using an encrypted messaging service, Padauk sends an 18-page dossier focusing on the Chinese-made Sinotruk vehicles that are ubiquitous in Myanmar – and the large German stakeholder in the Chinese company: the commercial vehicle manufacturer MAN.

MAN used to be a large conglomerate that included many different subsidiaries. Originally called Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg, the company also used to produce printing machines for the newspaper industry. At some point, it had a reputation for manufacturing ship engines and even tried its hand in the steel trade. Slowly but surely, though, the company narrowed its focus to the production of trucks and buses. The Swede Hakan Samuelsson, who headed the company from 2005 to 2009, was one of the first to realize that MAN should focus on its core business.

It was Samuelsson who engineered a notable, 560-million-euro deal back in summer 2009. It entailed the German company MAN acquiring a stake of 25 percent plus one share – an extra share that will become important in this story – in the Chinese truck manufacturer Sinotruk, which is listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange. "This important partnership is based on the good relationship we have had with Sinotruk for many years," Samuelsson said at the time. The head of the Chinese partner said the two companies would work "closely together to shape the future together."

They're the kinds of things that executives always say when they join forces with another company. But they are also soundbites that can become very problematic if they are later paired with images of brutal violence of the kind used against protesters in Myanmar. Scenes in which shots are fired at random into the crowd, in which specific protesters are pulled out and beat so badly they have to be taken to the hospital, in which security forces use slingshots to fire steel balls at demonstrators. And scenes in which trucks from Sinotruk can frequently be seen in the background.

The Süddeutsche Zeitung contacted both MAN and Sinotruk for comment about what it learned in the course of its reporting. Sinotruk did not respond to several emails, while a MAN spokesperson said the company first learned of the deployment of Sinotruk vehicles in Myanmar from our query. MAN, the spokesperson said, is now "examining the business activities involved." Furthermore, the company has "asked the Chinese partner to provide comprehensive information on business activities in Myanmar and to place the issue on the agenda of the early April meeting of the board of directors." It sounded as though the company had no knowledge of the situation and first had to gather information from Sinotruk.

The United Nations has accused the Myanmar

military of "systematic" attacks against the peaceful, mostly young

demonstrators – violence that includes both the random firing into crowds and

targeted killings as a way of fomenting fear and panic.

More than 400 protesters have been killed thus far, many of them by targeted gunfire. Last weekend alone, the military killed dozens of people, including several children.

"These are not the actions of overwhelmed, individual officers making poor decisions. These are unrepentant commanders already implicated in crimes against humanity, deploying their troops and murderous methods in the open," said Joanne Mariner, the director of crisis response at Amnesty International, in a report the group presented to the UN earlier this month. In compiling the report, Amnesty International analyzed more than 50 videos taken between Feb. 28 and March 8. Sinotruk vehicles can be seen in many of them.

Social media channels, especially Facebook and Twitter, are likewise full of photo and video material from the protests in Myanmar. Frequently, military vehicles from Sinotruk can be seen in the background of images showing the injured and dead. Sometimes, the trucks are in the middle of the demonstrations, at others they are parked off to the side.

A Twitter video dated March 15 shows a convoy of almost a dozen trucks transferring a military unit to Hlaingthaya Township in the western part of Yangon. According to local news reports, that neighborhood, too, was the scene of bloody skirmishes.

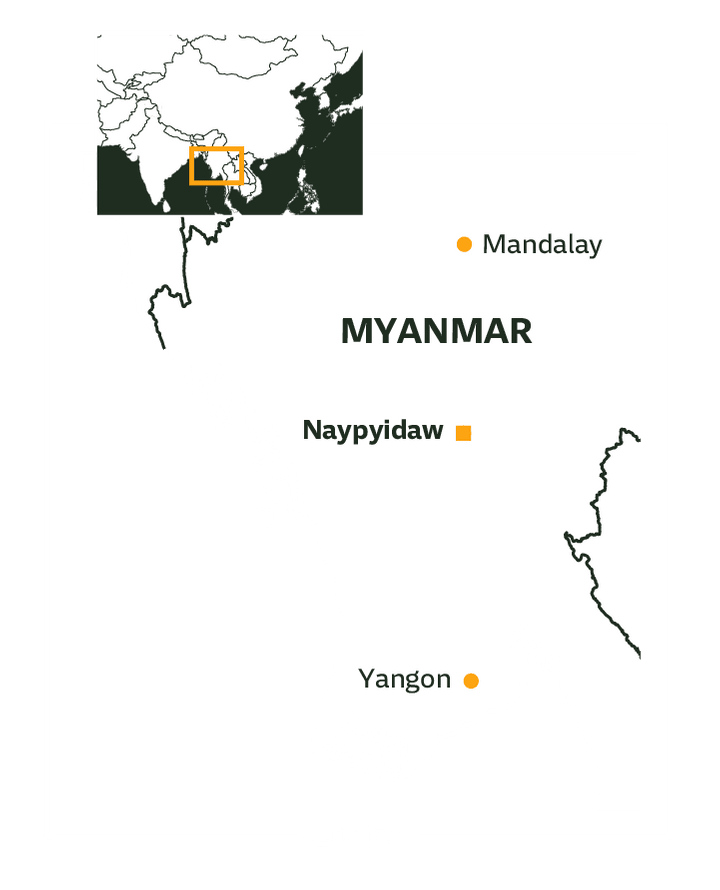

The Süddeutsche Zeitung examined around 40 photos and videos from Myanmar that included vehicles from Sinotruk. Most of them were from Yangon and Mandalay, but trucks from the Chinese company also confronted demonstrators in Naypyidaw.

The images provide clear evidence that the deployment of the Sinotruk vehicles has hardly been an exception. They are, in fact, the logistical backbone of troop deployment in the country and an essential element of the brutal approach the military junta has taken.

Sinotruk isn't the only foreign company that is earning money in Myanmar and thus supporting the military as it terrorizes the populace. The Munich-based company Giesecke & Devrient supplies Myanmar with banknotes. The inexpensive Swedish clothing retailer H&M relies on Myanmar-based factories. And the Japanese beer brewer Kirin owned a stake in a company that is under the personal control of the general who led the coup. Indeed, for years in Myanmar, it has been almost impossible to do business in the country without the involvement of the military.

Since the putsch, though, the military has clearly been committing human rights violations and shooting civilians. Every connection to the West can now be used to apply pressure. In fact, such links are the only levers available to activists in Myanmar. What company, after all, is interested in being linked to a murderous military junta?

In our communications with the activist Padauk – which took place both via text message and telephone conversations – he makes sure to obscure both his face and his true identity, concerned as he is about reprisals. Justice for Myanmar works as a collective, such that if one member is taken out of action, the others pick up the slack. In his discussions with the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Padauk requests a sense of urgency so that the world doesn't continue to ignore what is happening in his country – in the hopes that someone, maybe, will finally do something.

Padauk and his allies from Justice for Myanmar aren't shy about their intention of hurting the military by drawing attention from abroad, since they are virtually powerless inside the country. The group also publicizes the names of senior military junta leaders, their family members and businesses, some of who have since been sanctioned in the U.S. and the European Union – a strategy known as „social shaming.“

The information from Justice for Myanmar is quickly verifiable, particularly on Facebook – not only because the social media network has become just as important as the internet in Myanmar, but also because it has become the only way for halfway reliable information to get out of the country. The military has long since shut down those television stations it doesn’t control, and it has also cleared out editorial offices. This has made Facebook one of the most important platforms for the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), the group responsible for organizing the general strike against the military junta that has been going on for several weeks. It is also closely linked to Padauk’s Justice for Myanmar.

The activists are far flung. Many are still in Myanmar and are operating underground, while others are living, working and studying abroad. They include people like an activist in Bangkok who has given himself the pseudonym Jonas Tao Chin. He lives modestly in one of the more cheerful high-rise developments in the city, complete with a courtyard shaded by vegetation. Tao Chin says that the results of the last national vote in November, in which Aung San Suu Kyi was elected by an overwhelming majority, were a clear statement against military involvement in the government. “That’s why the generals conducted another coup,” he says. “At the end of the day, it’s always about money.” That is also where the protesters want to hurt the junta. And the general strikes are having an effect: Myanmar’s already beleaguered economy is in a state of rapid decline, which in turn means that money will soon grow tight for the military chiefs.

Protesters inside the country and their allies abroad quickly recognized that they had to use social media networks to attract international attention. “If it weren’t for the internet, they would be able to do whatever they want in the country,” says one exchange student from Myanmar who is currently living in the German state of Brandenburg. “They could also kill thousands of people each day.” His real name is known to the reporters, but we will refer to him in the article as Soe in order to protect him and his family. He had been looking forward to attending university in Germany, but then came the pandemic and the coup, and now he finds himself reading horrific new stories from his homeland every day, with a never-ending stream of reports about people being injured or killed. How is he doing? He laughs nervously before saying: "I'm pretty distraught."

The 29-year-old says that most of his friends are demonstrating on the streets of Yangon and that he writes them daily. “At the moment, no one is safe there,” says Soe. “The soldiers and police can knock on the door at any time and just arrest you.” He says they mostly come after dark, and that his friends sleep in different places every night. “When they take people with them, they say they are investigating,” he says. “But most of them come home dead.”

The social networks are now full of photos, videos and articles from Myanmar carrying the hashtag #whatshappeninginmyanmar.

The EU did move to impose an initial round of sanctions on March 22, but only against 11 military chiefs in Myanmar. Meanwhile, the British push for UN sanctions and for the international community to condemn Myanmar's generals failed because of vetoes by India, Vietnam, Russia – and China, the Myanmar generals' greatest ally.

And that brings the story, in a roundabout way, back to MAN. When the company bought shares in the Chinese company Sinotruk in 2009, it had long been known that China supported the Myanmar military, which had terrorized the country from 1962 to 2011 and never completely abandoned power even after that. And it was also known that Sinotruk's line-up of products included military vehicles. And MAN isn’t just some minor shareholder: The German truck-maker owns 25 percent of the company’s stock, plus one additional share. Under German laws pertaining to publicly listed companies, this is what is known as a blocking minority: It gives MAN the ability to stop important decisions.

There are also four delegates from Germany on Sinotruk’s board of directors. But they allegedly didn’t know about the deals with Myanmar. “The operational business is in the hands of the Chinese majority shareholder,” a MAN spokesperson explained.

In other words, no one at MAN is willing to take responsibility for what is happening in Myanmar. That’s likely why nobody is doing anything. Meanwhile, the striking protesters in the cities and villages are being shot at and, in some cases, literally executed. And soldiers continue to deploy using trucks from MAN's Chinese partner Sinotruk.

Over the weekend, the Munich-based company received a response from Sinotruk. According to officials at MAN, the letter stated it had been supplying vehicles and truck parts to Myanmar since 2008. It added, however, that there is “no cooperation whatsoever between Sinotruk and the current military regime in Myanmar.” In addition, according to MAN, Sinotruk provided assurances in its letter “that human rights have been and will be protected in the scope of its business activities in Myanmar.”