The Broken Heart of Africa

Michel fears the dogs more than anything. When he hears them panting and barking in the dark, along with the guards’ ominous, heavy footsteps, he grabs his hammer and chisel and runs. In his other hand, clutched tightly, is his loot: a sack full of rocks that are worth getting chased for.

Michel only wants to be identified by his first name. At 41, he has high cheek bones and eyes reddened by the dusty air. He sits in his living room in Kapata, an old miners’ settlement in the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo. It’s a place where trash piles up next to sandy ruts that were once streets and plaster flakes from the walls. Michel pulls a rock out of a plastic bag with his calloused fingers and rubs off the dirt to reveal a shimmering green. “Shaba,” he says in his native Swahili – copper. The green hue betrays that the stone is full of it.

Tobias Zick

He then pulls a second, grayish-black lump out of the bag – a piece of heterogenite that is rich in cobalt, an even rarer metal. “It’s in high demand and expensive on the international market,” he says.

The amateur miner must constantly trespass onto the grounds of a nearby mine to dig for these precious natural resources. The majority owner is one of the world’s largest players on the commodities market – the Swiss corporation Glencore. “What else are we supposed to do?” Michel asks. “We have no other choice if we want to get by.”

Michel’s home country, the Democratic Republic of Congo, is more than six times the size of Germany and is located at the heart of Africa. Precious Congolese metals are vital not only for laptops and mobile phones, but also for the energy revolution taking place on the world’s streets as mobility shifts from gasoline and diesel engines to electric cars. Cobalt and copper are needed for motors and charging stations – and Congo has an abundance of both. The country’s stockpiles have already inspired analysts to dub it the future Saudi Arabia of electromobility. Large concentrations of these metals are buried just beneath the surface.

Like all of Congo’s mines, the quarry that Michel regularly trespasses on used to belong to the state-owned mining company Gécamines. Michel’s father worked there as a chemist. And Michel himself began studying medicine – that is, until a plundering dictator drove the mining company into the ground. After that, a war broke out and the new government reallocated the country’s mining rights. More precisely, it squandered the country’s wealth by selling the best mines to foreign investors at prices far below market value. Ordinary Congolese, on the other hand – people like Michel – were left to fight over the scraps.

In order to better understand how mining deals in the Democratic Republic of Congo come to fruition, it can help to look back several years – in this case, to a hot Monday afternoon in June 2008 at the Zurich airport.

PR

Ten men had descended upon the Hilton Zurich Airport to discuss the future of the rich copper deposits known today as the Katanga mine – the same area where, years later, Michel would illegally mine at night until the dogs chased him away. The gathered men were members of the board of directors of a company called Katanga Mining. The Swiss corporation Glencore had already invested more than $150 million in the company at the time, but suddenly, big problems cropped up. The Congolese government had decided to renegotiate many of its mining contracts, since the permits had often been awarded at prices that were disadvantageous to the country. The already shaky talks began to fall apart. The gathered Katanga Mining board members agreed: Congo’s demands were “unacceptable.”

Minutes from meetings held at the time and internal contract documents are part of the Paradise Papers obtained by the Süddeutsche Zeitung. By analyzing the data, reading contemporaneous reports that are publicly available, holding interviews with experts and traveling to Congo, reporters with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) have reconstructed the events in what is no less than an economic thriller.

The protagonists are people like Michel, who spend their nights illegally digging into the earth of their homeland.

It all began on a summer day in Zurich. Unable to make any progress in Congo, the mining company’s board of directors asked someone for help, a man known for his strategic savvy in the raw materials business and for his close relationship to Congo’s president. The man's name was Dan Gertler, an Israeli businessman and scion of a diamond merchant family who had realized at the right time that copper and cobalt could be at least as lucrative as diamonds. If anyone could shift the negotiations in favor of the mine operator, it was him.

At the end of the tough negotiations, the country would forego several hundred million dollars it had initially demanded. The whole process back then has left Glencore with some explaining to do now, because a retracing of events with the help of the Paradise Papers raises the question of whether one or more Congolese politicians or officials were bribed over the course of the negotiations.

The wholesale sell-off of Congo’s natural resources began back in May 1997. Laurent-Désiré Kabila, for decades a notoriously unsuccessful militia leader, marched on the Congolese capital of Kinshasa with an army of rebels, including thousands of child soldiers. He had the support of two neighboring countries, Rwanda and Uganda, both of which had tasked him with deposing the dictator Joseph Mobutu, the epitome of the African kleptocrat. Kabila promised his followers he would help them realize an old Congolese dream of regaining control of their country’s riches – copper, cobalt and uranium – and using the proceeds for the benefit of the people.

Kabila’s foreign allies helped him achieve the breakthrough he yearned for. On May 29, 1997, he was sworn into office as president in a soccer stadium. “My long years of struggle were like spreading fertilizer on a field,” he said. “But now it is time to harvest.”

David Guttenfelder/AP

In retrospect, his words seem like a direct warning.

It was during Kabila’s presidency that a young Dan Gertler discovered Congo and went to Kinshasa. Prior to his arrival, he had traded diamonds in neighboring, civil war-ravaged Angola. Now he was on the lookout for new business opportunities. Kinshasa, once called “Kin La Belle,” or Kin the beautiful, had taken on the rather unsavory moniker of “Kin La Poubelle” under dictator Mobutu – Kin the trash can. The war had pushed the city over the edge. Putrid stenches emanated from open sewers, piles of trash burned along the sides of roads and legions of starving people meandered through the streets.

Gertler, however, would not be deterred. A rabbi introduced him to the head of the Congolese army, Joseph Kabila, the president’s son. The two young men became friends and soon Gertler would meet his father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

The president was under massive pressure at the time. Once in office, he had fallen out rather quickly with his protectors, Rwanda and Uganda. The very countries that had made his victory over Mobutu possible in the first place now wanted him gone, so they sent a new rebel army to topple him. But Kabila had no intention of going quietly, and he had other African powers behind him, including Angola and Zimbabwe. The war over Kabila’s grasp on power would go down in history as the “Great War of Africa,” and it is estimated to have claimed the lives of more than 3 million people. The war also drove the final nail into the coffin of the already dying copper industry. Production at the once magnificent state-owned mines had almost ceased entirely. Congo, the maltreated heart of Africa, was broken.

Kabila needed money to finance his troops in the war – lots of it. His primary source of foreign currency at the time was the export of diamonds – and Congo had plenty of them. Such stones are called blood diamonds if the proceeds from their sale are used to finance violent conflict. Merchants who buy blood diamonds risk being shut out of the international diamond market. At least in theory.

Gertler had the money that Kabila needed and he was on the lookout for diamonds.

Simon Dawson/Bloomberg

A confidential report by a global risk analysis firm, as quoted by Foreign Policy magazine, would later describe Gertler’s philosophy as such: “everyone has a price and can be bought.” Contacted by the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Gertler said he acted in strict adherence to the law in Congo and all other countries in which he does business.

It was the beginning of a perfect symbiosis. Laurent Kabila promised the young Israeli a monopoly on all Congolese diamonds if Gertler could quickly get him $20 million, a United Nations report would later maintain. In exchange, Gertler was to provide access to “fast and fresh money” that could be used for the purchase of much-needed arms. The report also stated that Gertler was to use his ties to Israeli generals to facilitate access to “Israeli military equipment.” According to the UN’s account, the deal turned out to be a “nightmare” for Congo. It also stated Gertler paid only $3 million of the $20 million that had been agreed to and never supplied the military equipment the country had hoped for. When asked, Gertler categorically refuted the UN’s account, saying he had not been questioned by the UN for the report.

Whereas Kabila had bargained away a chance for a better future for his country, this was the beginning of something big for Gertler. “When I do something, I do it,” the news agency Bloomberg once quoted him as saying. “I don’t sleep much. I don’t have a lot of nightlife or a lot of time just with friends. I’m just very, very focused on what I have to do.” Before long, he began commuting between the mine in Congo and his family in Tel Aviv.

On Jan. 16, 2001, President Laurent Kabila was shot and killed by one of his bodyguards. His son Joseph took up the throne, and his friend Gertler became a source of support for the new regime. Joseph Kabila even sent him as an emissary to peace negotiations with neighboring countries and the United States. Gertler had arrived at the center of power.

Desirey Minkoh/AFP

Joseph Kabila, the former army chief, didn’t know much about politics, but he was a highly gifted strategist. In addition to Gertler, he soon counted a young mechanical engineer by the name of Augustin Katumba Mwanke among his loyal followers. Like Kabila, Katumba hailed from the copper-rich south. He would later write in his memoirs that, even as a child, he had dreamed of one day becoming a kind of “God who would rule over all of decolonized Africa’s gigantic mining empire.”

Katumba came pretty close to realizing his dream when Kabila named him as minister of the presidency and state portfolio, a position that gave him power over mining licenses, even beyond his time in office. It was the beginning of a “plundering system,” as one former Congolese minister, Olivier Kamitatu, described it in an interview with the Süddeutsche Zeitung. Kamitatu has since gone over to the opposition. He says the Kabila-Gertler-Katumba team operated “in total opacity, without any transparency and without any accountability.”

Katumba ushered in the privatization of the state-owned Gécamines mines. The international community had demanded it so that hard currency needed for reconstruction could start flowing into the war-ravaged country.

Congo sold the mining rights for nearly all its copper reserves to private investors, but under terms and conditions that were devastating for the country. The report from a UN investigation described Katumba in 2002 as a “key power broker” for mining licenses among an “elite network” of officials, businesspeople and criminals that “transferred ownership of at least US$5 billion of assets from the State mining sector to private companies" in the past three years – with no compensation or benefit for the state coffers of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

An investigative commission in the Congolese parliament expressed concern in 2005 over the future of several copper mines that would later become a central part of the Katanga mine. It is believed to be one of the country’s richest copper deposits. At the time, parliamentarians called for licenses to be allocated publicly to prevent Congo’s valuable resources from being “plundered” again.

Their calls, however, fell on deaf ears. The rights for the mine went to multiple investors, including Dan Gertler. A World Bank expert expressed dismay in a later report over the “complete lack of transparency.” The licenses, the report stated, were awarded without a bidding process or disclosure of the deal’s conditions – a portrayal that Gertler denies.

According to Elisabeth Caesens, a Congo specialist with the American nongovernmental organization The Carter Center, all important deals at that time went through Katumba, meaning the agreement between him and Gertler was one among friends – or would it be more appropriate to say: among brothers?

Or, “my twin brother,” as Katumba described businessman Gertler in his memoirs. A photo of the two confidants apparently taken in an Israeli hospital shows just how close they were.

Katumba can be seen in a hospital gown with Gertler standing next to him and holding his hand. Katumba praised Gertler’s “inexhaustible generosity” in his autobiography, noting in one anecdote how Gertler had invited the Congolese politician and his wife on a cruise in the Red Sea. He also arranged for a private performance by Israeli illusionist Uri Geller, which Katumba described as a “surreal experience” for a “humble Congolese man” like himself. Gertler had secured Katumba’s admiration.

At the time the business relationship between Gertler and raw materials company Glencore was taking shape, the situation in Congo seemed more stable than it had been in a long time. In 2006, Joseph Kabila won a snap election and observers had even deemed the ballot relatively free and fair by Congolese standards. The president successfully quashed a subsequent armed uprising by members of the opposition. Former UN investigator Jason Stearns, a leading Congo expert, believes Gertler partly financed Kabila’s election campaign. In his book “Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of Congo and the Great War of Africa,” Stearns wrote that in interviews with representatives of the mining industry, everyone he spoke to told him “the same thing” – namely that Gertler and a further businessman “contributed considerably to Kabila’s campaign coffers, although both deny this.”

The Süddeutsche Zeitung requested an interview with Gertler on the subject of corruption allegations in Congo, but the interview never took place. In a written statement, Gertler referred to his engagement for the country's development. His companies are some of Congo’s largest taxpayers, he wrote, and created around 30,000 jobs. The statement insisted Gertler is a “respectable businessman” who obeys applicable law.

The fact that some might see things differently is suggested by a Justice Department document from 2016 in an action involving a U.S. hedge fund called Och-Ziff. Around the same time Glencore was securing its mining rights in Congo, according to the document, an “Israeli businessman” was allegedly also doing deals for Och-Ziff. As part of a deferred prosecution agreement, the hedge fund admitted bribes had been paid to the Congolese government to obtain special access to mines in the country.

Bribery payments of more than $100 million were made between 2005 and 2015 to government officials in Congo, the court document stated. It also identified one of the alleged intermediaries purported to have facilitated the bribes – the “Israeli businessman.” The document did not reveal the person’s identity, but it did provide the name of a company he controlled: Lora Enterprises. For years, the Israeli is alleged to have orchestrated millions in bribes to a politician referred to in the court paper only as “DRC Official 2.” But it does state the date of the man's death, Feb. 12, 2012.

That was the day Augustin Katumba Mwanke, the president’s right-hand man and something along the lines of the No. 2 in the hierarchy of Congolese power, died in a plane crash. Mwanke had also been a close friend of Dan Gertler. Gertler, meanwhile, an Israeli businessman, was behind a firm called Lora Enterprises.

The court document also described another occurrence in which it is believed that the unnamed Israeli played a role. In 2008, the man allegedly bribed a Congolese judge. In a text message, he instructed that his competitor must be “screwd (sic) and finished totally!!!!” In another email written at a later time, he boasted, “The DRC landscape is in the making and I am shaping it – like no one else.”

Gertler claims that the court document cited does not constitute any evidence against him, because the Justice Department action was solely directed at the U.S. hedge fund Och-Ziff. He claims he was not questioned in the case and rejects all allegations. Gertler alleges that some of the documents received by the Justice Department were “false and baseless.” He also categorically denies having had “improper, illegal and/or corrupt relations” with President Kabila or Katumba Mwanke. Gertler maintains that his friendship with Kabila had been strictly private in nature and that it was only after his time in office that he encountered Katumba on a “personal basis.” The Justice Department took no action against Gertler or any of his businesses.

Glencore holds a majority stake in the Katanga mine today. The Swiss commodities company had already been the subject of criticism years ago due to its relationship with Gertler. In a comprehensive report published in May 2014, Global Witness criticized Glencore’s financial and business entanglement with Gertler, the president’s friend, in copper deals in Congo. The globalization-critical organization wrote of “obvious corruption risks.” For their part, Glencore and Gertler defended the deals at the time, asserting that they were totally clean. One year earlier, Glencore CEO Ivan Glasenberg issued a blanket denial of all corruption allegations, which he dismissed as “empty claims.” In an interview with the Swiss newspaper Sonntagszeitung, he said, “Nobody has delivered any evidence. I could also make claims that someone had committed some crime or another. I’m fighting against corruption. There is zero tolerance at Glencore.”

Fabrice Coffrini/AFP

For a reporter trying to see the Glencore mines in Congo first-hand, the journey is a long one: It requires countless telephone calls, emails and negotiations with a company spokesman. There are also follow-up questions: What exactly do you want to see? Why are you so interested in mines in faraway Africa?

Following weeks of discussions, the company agrees to show the reporter around. The Switzerland-based spokesman, however, insists on tagging along. The two meet late one night at the Frankfurt airport. The spokesman is a tall, amiable man in his late thirties, a PR professional from London who knows all of the most important books on Congo’s history. It’s an overnight flight to Johannesburg, South Africa, followed by a connecting flight on a small charter jet. The Glencore plane flies three times a week directly to Kolwezi, the city located in the heart of Congo’s copper region. The small airport was expanded by Glencore itself.

On the way to the mine, the company-owned Jeep crosses a newly built bridge that Glencore also helped finance with $10 million, as the spokesman offers as an aside. He says the company is facilitating the country’s development and that many additional examples of its patronage will be seen on the trip.

At the Katanga mine, a massive, stepped pit has been dug deep into the earth. A quiet hum can be heard emanating from the depths as excavators and trucks are loaded with debris. Seen from high above, they look like miniature Tonka toys. A mustachioed man in a safety vest puffs on an e-cigarette as he watches the activity below. “This is a heck of a deposit,” he murmurs in American English. His name is Johnny Blizzard, and he has spent the last two and a half decades working in mines in the U.S., Chile and Mauritania. Today, he’s the chief operating officer at the Katanga mine in Congo.

When Glencore acquired the mine in 2009, Blizzard says, the pit had been largely underwater. The company is currently in the process of overhauling operations at Katanga mine to make it one of the world’s largest suppliers for the boom in electric cars. Soon, some 300,000 tons of copper and 22,000 tons of cobalt are to be extracted a year. “It’s going to be a lot of fun,” Blizzard says.

Tobias Zick

A signpost standing next to him bears arrows pointing in every direction: Brussels, 7,113 kilometers; Toronto, 12,002 kilometers. Baar, the small Swiss city where Glencore is headquartered, is 6,619 kilometers away. The last one provides a subtle reminder of where the true power lies.

As they tour the mine together, the reporter asks the Glencore spokesman about allegations critics had been raising for years about the relationship between Gertler and Glencore. Was corruption ever involved? Rather than a clear “yes” or “no,” the spokesman insists on a single formulation up to the very end: “Glencore is committed to uphold good business practices, to apply Glencore’s standards and policies to our activities and to meet or exceed applicable laws and external requirements.”

Throughout the Congo trip, the spokesman prefers to talk about other issues. Much of the two-and-a-half-day tour is spent hearing about social projects the company is financing that relate to the mine. There’s a company hospital, for instance, in which all employees and their families can get treatment for free. There are also filter systems for drinking water as well as books and computers for a college. Everything is financed by Glencore, including the motor-operated pumps that spray water onto a field as a group of women from the village sing and dance for the Glencore representatives and the reporter. They are grateful, one woman says, that they no longer have to dig for copper ore with their bare hands and can instead sell tomatoes at the local market.

As if on a classic African safari, evenings are spent with the Glencore representatives in outdoor restaurants in a company-owned lodge, where the fake elephant, hippo and warthog trophy heads seem deceptively realistic. Only, it’s not herds of gnus one sees against the night sky here, but transformers. As they talk shop over gin and tonics, it isn’t the number of leopards, lions or buffalos seen that day that dominate the conversation, but the latest jumps in the price of copper and cobalt because of the electric car boom. An air of contentment was discernible.

Contentment, by contrast, was in short supply nine years ago on that hot June day in 2008 at the Hilton Zurich Airport. The 10 Katanga Mining board members were troubled by the fact that negotiations with the government of Congo over mining licenses had stalled. The mining company was fighting for control over Katanga’s copper riches. At the time, Glencore already held an 8-percent stake in the mining company and supplied one of the board members.

Because talks with the Congolese government weren’t going well, the board turned to Dan Gertler for help. Gertler also held shares in the mining company and had excellent contacts within the Congolese leadership. The company gave him a written mandate to negotiate with “DRC authorities,” according to the meeting minutes, just one of the hundreds of pages of internal board minutes about the Katanga mining operation that can be found in the Paradise Papers. Glencore’s envoy, a confidant of CEO Glasenberg, backed the mandate.

Gertler accepted the assignment and found success: Just 17 days later, the differences with the Congolese had been cleared up. The minutes for the next meeting on July 10, 2008, show that members of the board showered their intermediary with praise. “Dan Gertler had fulfilled his mandate very well," and "the meetings over the last 2 days had been extremely productive.” The outcome, the notes indicate, had been “very positive.” The board was almost festive in thanking “Mr. Gertler for bringing it about.”

When contacted with information gathered in the reporting of this article, Glencore confirmed for the first time that Gertler had in fact been given the mandate for negotiations with the authorities in Congo. It is a delicate situation, given that a joint confidant of Gertler and President Kabila had also gotten involved -- namely Augustin Katumba Mwanke. He was none other than the “DRC Official 2” named in the other court case involving the U.S. hedge fund Och-Ziff, the one who had allegedly received bribes through an “Israeli businessman” for a total of $18.5 million. The court documents show that the alleged payments were stretched out over a period of three months. They took place at almost the same time that Glencore and the other shareholders were encountering their difficulties.

This raises the question of whether methods similar to those allegedly used in the Och-Ziff case were used to clear up the differences over the Katanga mine. “At the time, any major decision about Gécamines’ assets would require Katumba’s approval,” says Congo expert Elisabeth Caesens, who recently published a book about the privatization of the country’s mines. “Katumba had more power over Gécamines than the minister in charge of state-owned companies.” But Gertler claims that all negotiations were conducted in a “bona fide manner” and with the appropriate professional distance.

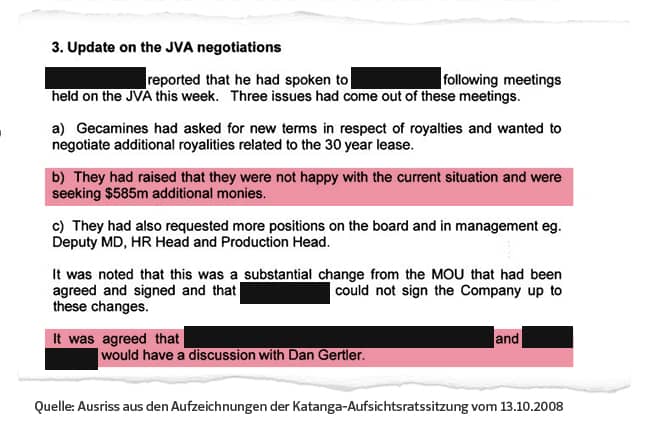

The Katanga board members’ euphoria over the agreement with the Congolese would prove premature. It wasn’t long until the new CEO of the mining company, now a man from Glencore, had to report the next crisis to the board on Oct. 13, 2008. The Congolese were now demanding additional money, saying that the sum should be based on the actual reserves in the mine.

An excerpt from the minutes of the Katanga board meeting on Oct. 13, 2008The meeting notes state that the Congolese “were not happy with the current situation were seeking $585m additional monies (sic).” That sum was much too high for the Katanga mine board members. They decided that four of them, including the Glencore representatives, would “have a discussion with Dan Gertler” immediately.

Glencore has confirmed that price negotiations did, in fact, take place in 2008. According to the Swiss company’s version of events, the Congolese government and Katanga Mining had already agreed upon a payment of $135 million before Gertler even got involved. But then Congo suddenly demanded more money.

Gertler also says that the amount asked for by the counterparty was much too high, and that no negotiator would have accepted the $585 million sum Congo had demanded. Both sides made concessions and the Congolese ended up in a better situation than they had been in, he says. Ultimately, Gertler says, there was no basis for the allegation that his efforts resulted in inadmissible preference for Katanga Mining. In the end, Congo wound up getting $140 million instead of the $585 million it had originally demanded.

Mining expert Caesens, who has spent years studying such transactions and has compared the numbers, believes that Katanga and Glencore got a huge discount. “Katanga paid four times less per ton for its mining permits than the amount almost all other investors in the Congolese copper sector agreed to pay,” she says. In other words, Congo sacrificed hundreds of millions of dollars – and helped Glencore save a ton of money.

Neither the Congolese government nor the state-owned mining company would or could explain why Glencore only paid a quarter of what Congo had temporarily demanded. Or why the impoverished country would forgo money that it really could have used.

Katanga had ordered a solution to their problem and Gertler had delivered.

But just who had Glencore gotten involved with? What could the Swiss company have known back then, in 2008, about Gertler, the man negotiating on its behalf in Congo?

It should be recalled that the UN report which described the business dealings of a Gertler firm in Congo as a “nightmare” had already been made public back in 2001. In 2005, the Congolese parliament concluded that a Gertler-controlled company had provided the state-owned mining company Miba with a loan with what it described as usurious conditions. There’s also the Och-Ziff episode, which first came to public light in 2016 and which seems to cast serious questions about possible corruption on Gertler.

“Glencore’s compliance division should have stopped this partnership with Dan Gertler,” says Mark Pieth, an internationally respected Swiss corruption expert. “I see only two possibilities: Either Glencore didn’t perform due diligence on Dan Gertler or they knew very well that there was a corruption risk – and deliberately accepted it.”

Further details about Gertler’s dealings in Congo have been released publicly in recent years. In May 2013, an expert panel chaired by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan determined that Congo squandered mining rights in five dubious deals between 2010 and 2012 by selling them at undervalued prices, and is estimated to have lost at least $1.3 billion – “equivalent to twice its annual spending on health and education combined.” The report claims that a Gertler company was involved in all of these deals. Gertler categorically refutes all the allegations made by the Africa Progress Panel and says his company was not given the opportunity to respond to any of the allegations against it.

Glencore acquired Gertler’s shares in the joint mines in February 2017. Industry experts view this as an attempt by the Swiss corporation to distance itself from Gertler and thus protect its reputation. Gertler himself says he retains contractual rights to receive licensing fees in connection with the Glencore mines in Congo. Not a bad deal either: On the global market, cobalt is one of the “hottest commodities of 2017,” according to an analysis by the bank UBS.

After the tour of the Congo mines, and after parting ways with the Glencore spokesman, a massive sign could be seen on the side of the road with a mustachioed Kabila smiling at his people. “My Congo,” it read, along with: “Even if you don’t want to believe in me, at least believe in my achievements.”

Next to his photo is a large image of the bridge that Glencore partly financed.

And what does Michel, the small-time prospector at the edge of the Glencore mine, expect for the future? Does he hope that the old Congolese dream will someday come true and the country’s mineral resources will one day help the people? If that happened, would he perhaps like to return to his medical studies?

Michel lets the rocks, the copper and cobalt ore, slide back into the plastic bag. “It’s too late for that,” he says. “I’m 41 now. I have to provide for my children. I can’t stop working.” His dreams have grown smaller with the passage of time. “If Glencore were to give me a job,” Michel says, “a full-time position with a salary. That would be something.”

Statement from Dan Gertler

Prior to publication on Sunday, and without knowing what the Süddeutsche Zeitung had written about his business dealings in Congo, Dan Gertler’s lawyer provided the following statement:

This is the response of Mr. Dan Gertler to the media campaign waged against him in recent weeks by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

We require you to publish the following response as is, in full, and without editing it.

If you wish to edit something in it - you must receive our permission to do so, in writing. This response comes in addition to responses that we have already sent you to the questions and issues that you raised before us.

The response follows:

Response to the broadcast/printed press

"The article presented to the public is the product of unrestrained and unbalanced journalism. Put simply, the article misleads the public entirely about Mr. Gertler’s business activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The article is devoid of complete and accurate facts. It is a jumble of claims based on erroneous assumptions, gossip and regrettably, incorrect inference and speculation.

Mr. Gertler and the Fleurette Group always perform their business affairs for sound commercial reasons and on an arm’s length basis. The innuendo arising from the article stems from a complete lack of understanding of the transactions described, the business environment in which they were carried out and their economic contexts. The article is also strewn with incorrect interpretations of incomplete documents that were stolen from attorneys’ offices.

It is extremely disturbing that, due to the ICIJ’s failure to understand complex business matters, particularly international finance transactions and the standard documentation that accompany them, the authors have come to misleading and erroneous conclusions. All finance documents the ICIJ have referred to were drafted and negotiated by leading international law offices from both sides. These documents were based on international standards, with provisions reflecting international norms.

It is also troubling that the authors refused our request to arrange a meeting between Mr. Gertler and the representatives of the press consortium over the last month, in order to address various issues mentioned in the article and to present the consortium with additional documents and information. Their continuing refusal was made on claims of impossible timeframes and spurious legal excuses. This is a breach of the good faith required of every journalist and goes to demonstrate their insistence on adhering to conspiracy theories that lack any foothold in reality.

The public should know that the DPA settlement executed by the Och-Ziff hedge fund was executed without Mr. Gertler's knowledge, consent or involvement, in any way or manner whatsoever. To the extent that it referred to Fleurette Group business in the DRC, Mr. Gertler rejects the factual narrative set out in the DPA in its entirety. Furthermore, Mr. Gertler has never been interrogated or asked to appear in front of the US authorities to provide any account on the matters referred to in the DPA.

Mr. Dan Gertler is a respectable businessman who contributes the vast majority of his wealth and time to the needy and to different communities amounting to huge sums of money. As at January 2017, Fleurette’s subsidiaries and partnerships support around 30,000 jobs in the DRC and are amongst the DRC’s leading taxpayers, contributing significant revenues to the State. Fleurette is also a major contributor to social development in the DRC through the Gertler Family Foundation (GFF) and through direct investment in social infrastructure. The GFF is the largest charitable organization in the DRC, funding more than 50 programs and projects across the DRC, which help tens of thousands of Congolese every year

Statement from Glencore and Katanga

In addition, the Swiss corporation Glencore issued the following statement on Thursday, Nov. 2, likewise prior to publication of the Süddeutsche Zeitung report, about its business dealings in Congo and its cooperation with Dan Gertler:

ERKLÄRUNG VON GLENCORE UND KATANGA, NOVEMBER 2017

Hintergrund

Im Juni 2007 erwarb Glencore eine Beteiligung an Nikanor Plc (Nikanor). Nikanor war ein börsenkotiertes Unternehmen am „Alternative Investment Market“ (AIM) in London. Glencores Anteil an Nikanor lag vor Nikanors Fusion mit Katanga Mining Limited (Katanga) bei 13,88%.

Im Januar 2008 fusionierten Nikanor und Katanga. Die Fusion resultierte in eine Umwandlung von Glencores Anteil an Nikanor in Höhe von 13,88% in einen Anteil in Höhe von 8,52% an der neuen kombinierten Gruppe.

Die Hauptbetriebsgesellschaft von Nikanor in der Demokratischen Republik Kongo (DRC) war die DRC Copper und Cobalt Project (DCP). Die Hauptbetriebsgesellschaft von Katanga war die Kamoto Copper Company (KCC). Die staatliche Bergbaugesellschaft Gecamines war mit 25% an den Unternehmen KCC und DCP beteiligt. Zum Zeitpunkt der Fusion war DCP im Besitz verschiedener Abbaugenehmigungen und Schürfrechte in der Demokratischen Republik Kongo, die im Februar 2006 an DCP übertragen wurden. KCC wurde 2005 gegründet und leaste die Abbaugenehmigungen und Schürfrechte von Gecamines gemäss einer Joint-Venture-Vereinbarung vom Februar 2004.

Joint-Venture-Vereinbarung

Gegen Ende 2007 nahm Katanga mit der staatlichen Bergbaugesellschaft Gecamines Verhandlungen auf. Diese zielten darauf ab, DCP in das KCC-Joint-Venture zu konsolidieren.

Im Februar 2008 schlossen Katanga und Gecamines eine Vereinbarung über die Übertragung bestimmter Abbaugenehmigungen und Schürfrechte von Gecamines an KCC, eine Tochtergesellschaft von Katanga, ab. Diese Vereinbarung vom Februar 2008 sah die Zahlung eines „Pas De Porte“ (Ablöse) an Gecamines vor, das auf der Grundlage der in einer Machbarkeitsstudie ausgewiesenen Kupferreserven von KCC berechnet werden sollte. Katanga gab im Februar 2008 bekannt, dass der gemäss dem vereinbarten Grundsatz zu zahlende Betrag sich auf rund 135 Millionen US-Dollar belief. Ferner stimmte Katanga zu, beträchtliche Kupfer- und Kobaltreserven an Gecamines mit einem geschätzten Wert von 825 Millionen Euro freizugeben. Gecamines stimmte zu, Ersatzreserven bereitzustellen oder, falls Gecamines dazu nicht in der Lage wäre, eine Entschädigung an Katanga zu zahlen.

Anschliessend leitete Katanga Verhandlungen mit Gecamines über die Umsetzung der im Februar 2008 geschlossenen Vereinbarung ein. Der Verwaltungsrat von Katanga beschloss im Juni 2008, Herrn Gertler zu bevollmächtigen, auf der Grundlage der Vereinbarung von Februar 2008 mit den Behörden der Demokratischen Republik Kongo zu verhandeln. Herr Gertler hielt eine wesentliche Beteiligung an Katanga. Im Laufe der Verhandlungen diskutierten Gecamines und Katanga den Umfang der Reserven von KCC, die gemäss der Vereinbarung von Februar 2008 bei der Berechnung des Pas De Porte zu berücksichtigen waren. Im weiteren Verlauf der

Verhandlungen legte Gecamines verschiedene Standpunkte zum Pas De Porte dar, der ihrer Meinung nach von KCC zu zahlen sei, einschliesslich war die Rede von Summen über 585 Millionen US-Dollar und 200 Millionen US-Dollar. Katanga vertrat erfolgreich ihren Standpunkt, dass die zuvor von Katanga genannte Summe im Wesentlichen korrekt war und dem im Februar 2008 vor der Bevollmächtigung von Herrn Gertler vereinbarten Grundsatz entsprach, nämlich dass der Pas De Porte nur für die Abbaugenehmigungen und Schürfrechte gelten solle, die tatsächlich an KCC übertragen worden waren. Im Juli 2009 wurde ein Joint-Venture-Vertrag zwischen Katanga und Gecamines geschlossen, der die Zahlung eines Pas De Porte von 140 Millionen US-Dollar vorsah.

Finanzierung

Im November 2007 gewährte Glencore Katanga ein konvertierbares Darlehen in Höhe von 150 Millionen US-Dollar. Während der Finanzkrise im Januar 2009 beschloss Glencore die Summe des konvertierbaren Darlehens auf 265 Millionen US-Dollar zu erhöhen.

Im Februar 2009 vergab Glencore Finance (Bermuda) Ltd ein Darlehen an Lora Enterprises Limited (Lora), ein Unternehmen, das mit Herrn Gertler verbunden ist. Die Abwicklung des Darlehens erfolgte durch die Übertragung einer Beteiligung am konvertierbaren Darlehen, das Glencore Katanga bereitgestellt hatte. Das Darlehen an Lora wurde zu marktüblichen Konditionen vergeben. Das Darlehen war mit angemessenen Sicherheiten ausgestattet (einschliesslich eines Pfandrechts an den entsprechenden Katanga Aktien), welche bei den zuständigen Registrierstellen eingetragen wurden. Im Jahr 2010 wurde das Darlehen von Lora vollständig zurückgezahlt.

Im Mai 2009 kündigte Katanga eine Bezugsrechtsemmission in Höhe von 250 Millionen US-Dollar an, an welche sich Glencore beteiligte.

Im Juni 2009 wandelte Glencore ihr konvertierbares Darlehen an Katanga um und erwarb einen Mehrheitsanteil an Katanga. Nach der Umwandlung des konvertierbaren Darlehens und der Bezugsrechtsemmission an Katanga, die im Juli 2009 vollendet war, hielt Glencore ungefähr 77,9 % an Katanga.