All people are equal, regardless of their skin color or religion, their salary or gender. And that's great, at least when it comes to career advancement, childcare or taking out the trash. But in terms of medicine, treating men and women the same is less advantageous. Yet it happens all the time – far more than it should.

Doctors treat women just as they do men, and the consequences are fatal – for women.

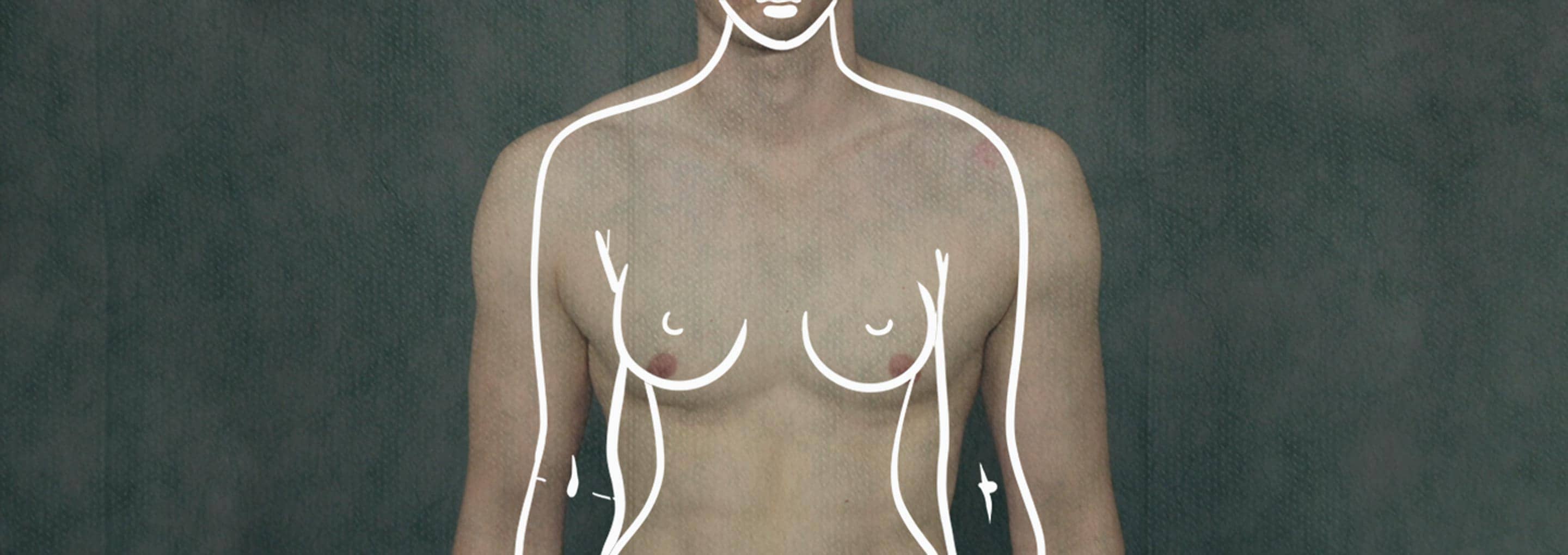

This in the field of medicine, an area in which there are real physiological, anatomical and hormonal differences between the genders – differences that are rarely taken into consideration. This leads to an array of adverse health effects for women that stem from sheer ignorance. Ignorance of the fact that women and men are simply not the same.

Heart attacks in women are frequently overlooked, for example, because their symptoms tend to be different. Whereas men often feel chest pain, women experience shortness of breath, nausea or vomiting. The side-effects of prescription drugs are also 70 percent more likely to affect women than men. Perhaps unsurprisingly, women also suffer disproportionately from malfunctioning medical devices. Indeed, they basically suffer from those deficiencies in two different ways.

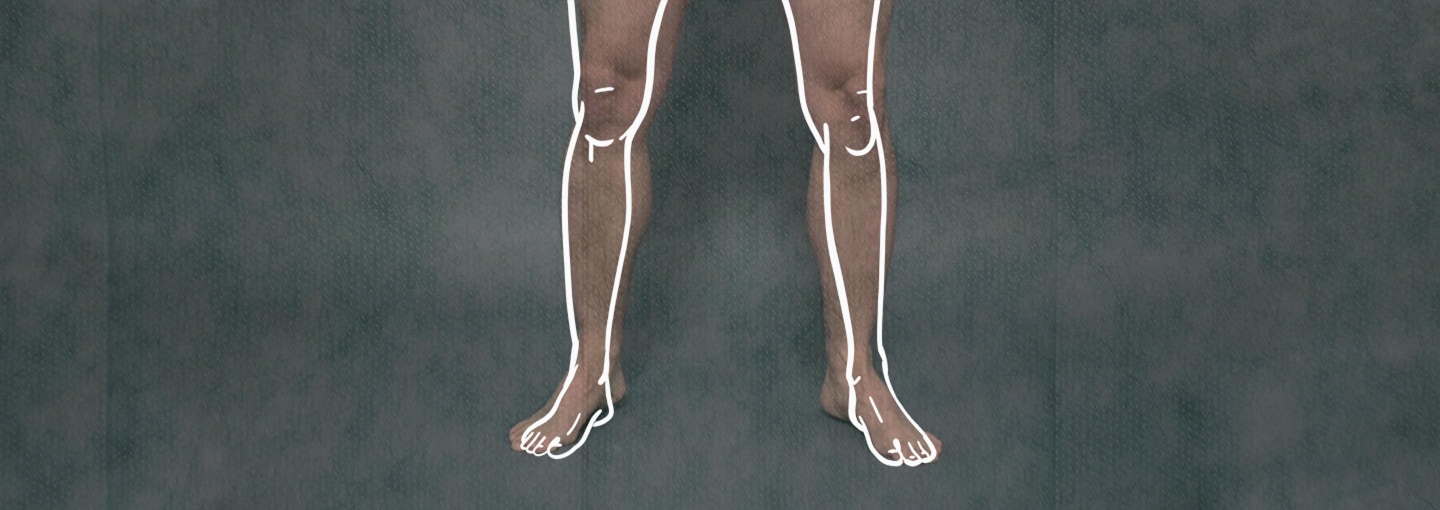

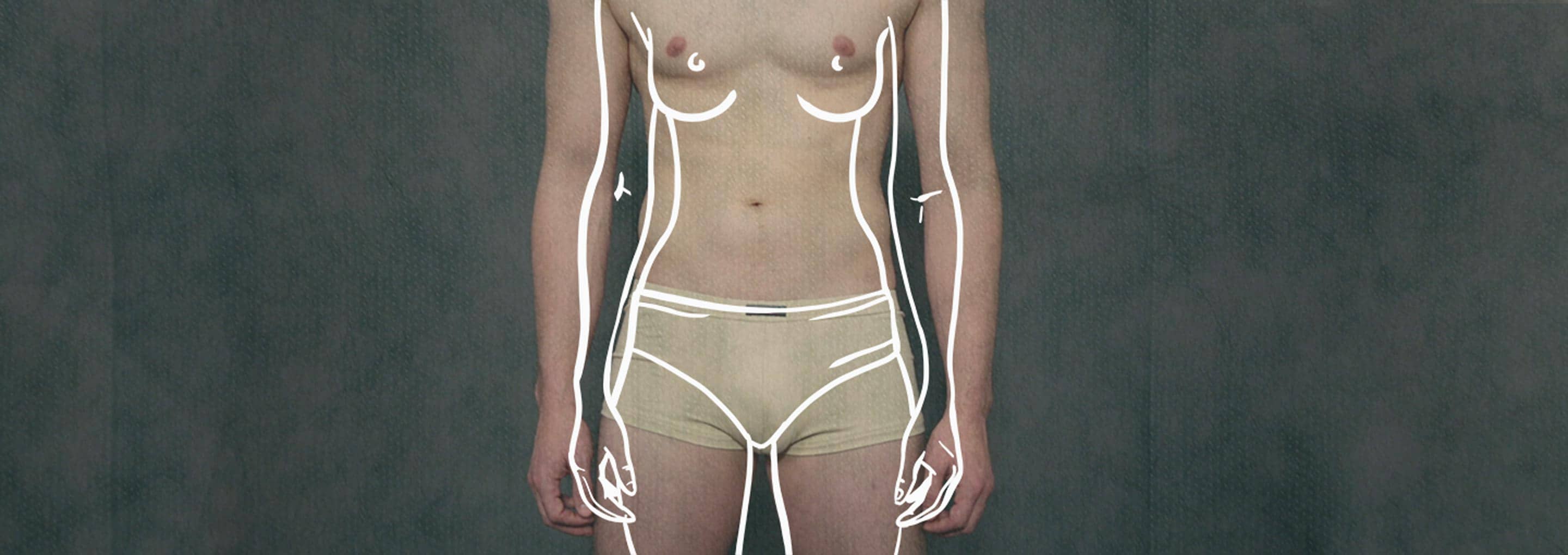

In medicine, being male is still considered the norm – a norm from which women deviate in ways that have not been sufficiently studied. That's why the tendency is to treat everyone as if they were male. Even the model skeletons found in doctors' offices and anatomy classes are almost always male – as if wide pelvises and narrow shoulders were merely a fluke of nature.

mauritius images / Chris Pearsall / Alamy

With this male image of the human body in mind, doctors often prescribe women medical devices that are designed for men. Many devices, prostheses and implants are developed by men, with men and for men. Women are frequently afterthoughts, not considered until the time comes to market the device. Until then, gender differences hardly play a role. But if the benefits and risks of a medical device aren't weighed against one another with an eye to gender differences, of course no such disparities will be found.

One reason negative consequences for women seldom stand out to developers and users is because women are all too often underrepresented in the studies evaluating the devices. In studies undertaken by manufacturers of strokes and heart attacks, for instance, often only 30 percent of test subjects are women. In one recent study for a modern pacemaker, known as CRT, only 20 percent of the test subjects were female. So, when women suffer disproportionately from a certain side-effect, or when a drug doesn't actually help them at all, it's statistically less likely they will be heard.

Ultimately, women are written off as exceptional and given the same treatment as men.

This male view of a male-dominated world is largely rooted in history. Young men, most often students, in the past, were generally ready and willing to help professors who wanted to test their inventions at the universities. There are also other explanations for the researchers' tendency to experiment on male patients: Manufacturers of medical devices as well as pharmaceutical companies are afraid of accidentally testing their products on pregnant women and thus risking the life of an unborn child. Such concerns are justified, as shown by the scandal over thalidomide, a drug thought to be a harmless sleeping pill but which caused massive birth defects in thousands of children in Germany in the late 1950s and early 1960s. But in an era of pregnancy tests and birth control, a solution must be possible. No longer justifiable at all, by contrast, is the notion that the focus should be entirely on men because they are the breadwinners. And another reason for excluding women from scientific studies is also indefensible: companies' fears that women's menstrual cycles and hormonal fluctuations could influence study results.

And here's where it gets cynical: It is apparent to all that the female body is different in some ways, but rather than testing products for how they interact with those differences, women and all their pesky hormones, pelvic tilt and coronary arteries are simply left out – as if these features are more nuisance than nuance.

Once a medical device goes on sale, women are, of course, an appealing market. In some parts of the body, they get even more device implants than men. Just under two-thirds of all artificial hip and knee joints are implanted in women.

That could, in part, be because women live longer and their joints are formed differently, making them more prone to deterioration. But female patients often have trouble with implants specifically because many prosthetics are developed for men.

The "Gender Knee" That Doesn't Fit

For years, female patients with new knee joints have had more problems with prosthetics than their male counterparts, such as when they climb stairs or kneel down. It's also more common for their artificial joints to loosen because women's knees are smaller and have different proportions. One American company developed a knee prosthesis based on data in which women were underrepresented and would then go on to rectify its mistake – using its late realization for PR purposes and advertising a new "gender knee." But the gender knee didn't offer any advantages for women, at least not in the first three years. The unsurprising conclusion to be drawn from this history? Just as shoe stores need to stock all different sizes, one-size-fits-all doesn't apply to women's knees either. What all women need are knees that fit.

At the same time, women who received a "gender knee" could count themselves lucky that the prosthesis didn't do any additional damage. Other women have not been so fortunate when it comes to supposed medical innovations.

Prone To Alignment Change

Since the late 1990s, artificial hips with large-diameter heads have been very successful. They have a shorter stem, which means surgeons don't have to drill into the femur as far to implant the device. But the pieces that are then hammered into the hip bone and the femoral neck are larger than with other prostheses. For women, who have smaller bones than men, this is not only impractical – it can be dangerous too. They are prone to alignment change, which can lead to further problems.

But manufacturers and doctors have long ignored these facts. In 2010, national joint registries in Sweden, Great Britain and Australia showed that women with these implants were 2.5 times more likely to require a follow-up operation than those with classic hip prostheses. Yet women still continued to receive the oversized implants for five years before the company finally recalled them.

Excluded From Innovations

Artificial hearts and pacemakers are often too big for women's bodies too. "At first, devices for mechanical circulatory support were always too large for women and caused problems," says Vera Regitz-Zagrosek, a cardiologist at Berlin's Charité hospital and pioneer of gender medicine in Germany. Some artificial hearts were more likely to cause hemorrhaging or strokes in women. The Heart Mate II model, for example, was tested on three times as many men as women before it was brought to market. One study of close to 500 male and female patients showed the device was twice as likely to cause strokes in women than men.

When real innovations actually do happen, woman are often excluded. Female patients, for example, receive modern, advanced pacemakers less often than men. Yet such devices are more beneficial to women than males: Their mortality rates after such procedures are lower, follow-up operations less frequent and their quality of life is higher.

Why Are Women Provided with Inferior Care?

Women typically earn less money and have worse health insurance. Women are also less likely to urge their doctors to prescribe them the newest models. And women are taken less seriously by doctors, a fact that gender medicine experts have long known. This often leads to severe physical maladies being overlooked and dismissed as psychological problems, says Alexandra Kautzky-Willer, an internist and the head of the gender medicine unit at the Medical University of Vienna.

Instead of providing them with the treatment they need, doctors have a penchant for prescribing psychotropic drugs, a legacy that goes as far back as the 1960s, when Valium carried the nickname "mother's little helper." "Even today, women are prescribed psychotropic drugs two to three times as often as men," says health researcher Gerd Glaeske, a professor for pharmaceutical drug safety at the University of Bremen. One could be forgiven for getting the impression that it's the female psyche itself that needs to be treated.

At least when it comes to gynecological products, one might think, the male-female problem shouldn't make itself felt. After all, such devices were designed specifically for women. But even when manufacturers target women directly, the outcome can be dangerous. They market things like intrauterine devices or breast implants, and the consequences can be anything from infertility and hormonal disorders all the way to cancer. This is the second way women suffer particularly from medical devices.

Silicone breast implants, for example, can threaten women's health. "Research clearly shows that implants are associated with significant health, cosmetic and economic risks," writes Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research in Washington, D.C. "And long-term risks remain unknown because no proper scientific studies have been conducted." Breast implants filled with silicone have been available since the 1960s. They weren't very popular at first, but beginning in the 1980s, back when shoulder pads were en vogue, women also increasingly started getting breast enlargements. But while shoulder pads only injured the collective aesthetic sensibility, silicone implants can actually be physically harmful.

One in four women who underwent breast reconstruction surgery after cancer treatment had to have a follow-up operation within seven years. For women who underwent cosmetic breast augmentation, it's one in eight. Those statistics are taken from a recent study of just under 100,000 American women who have received breast implants since 2007. The report notes that half of women who underwent breast reconstructions suffered from complications within the first seven years, as did one in three who had breast augmentation surgery. Often the women were unhappy with the results of their operations, or their bodies' immune systems fought the implants with a painful process known as capsular contracture. But material weaknesses frequently caused problems as well: The implants ruptured in 8 to 16 percent of patients.

Stefanie Preuin

Women also have reason to fear medical devices designed specifically for obstetrics. Take vaginal mesh implants, which are intended to firm up pelvic floors that have been stretched through childbirth, for example. Because pelvic tissue grows together with the mesh, women often suffer discomfort, pain or vaginal shortening. In the worst case, the ovaries or uterus must be removed.

Particularly topical right now is the scandal surrounding Bayer's birth control implant Essure. The device is comprised of two metal coils that are inserted into the fallopian tubes, but it can also trigger serious side-effects, including heavy vaginal bleeding, fatigue, incontinence and depression. Thousands of Essure patients have had to have their uteruses removed. Bayer has since taken Essure off the market in Europe and will discontinue sales in the United States starting in 2019. When contacted for comment, however, the company claimed that the device is safe and effective.

For the last few years, Essure patients have had a well-known activist championing their cause: Erin Brockovich. In 2015, the Americanconsumer advocate and environmental activist, whose battle against contaminated drinking water was immortalized in the film of the same name, with Julia Roberts in the leading role, asked Australian television: "How many women have to be harmed before we stop? I'd love to see the headline '20,000 Men's Penises Fall Off.' I'm telling you, the world would stop."

By Christina Berndt and Mauritius Much