Medical devices can perform almost biblical miracles. Artificial hip joints, lens replacements and hearing aids can make the paralyzed walk again, the blind see and the deaf hear. A growing number of people are using these aids, and the technology is becoming increasingly sophisticated. There is no doubt that medical devices – whether stents, insulin pumps or knee joints – save and prolong lives and improve life quality. And it's not just the elderly who benefit. Germany's Federal Association for Children with Heart Disease (BVHK), for example, once declared that children, and not adults, have the most to gain from pacemakers. The devices, the association said, allow them to romp around just like their healthy counterparts and the technology gives them the gift of a "long life."

But these high-tech products have a dangerous side when they are developed negligently with deficient regulation – when, in other words, inferior products wind up in the body. And there seems to be little public awareness of the issue. Governments, in particular, often seem to behave as though it is not their problem.

In cooperation with around 60 media outlets around the world, including the public broadcasters NDR and WDR in Germany, the Süddeutsche Zeitung spent over a year reporting on the issue. The findings from that research will be published in the coming days as part of the "Implant Files." They are alarming, showing that the implantation system is defective, prone to manipulation and responsible for countless deaths.

Medical devices are a multibillion-euro industry. Germany's Federal Health Ministry estimates the volume of the global market at around 282 billion euros annually. German companies alone generate annual sales of 30 billion euros.

Some 210,000 people work in the industry in Germany. After the United States and China, Germany is the third-largest medical device market in the world.

As such, one might think that medical devices would be subjected to the same strict and independent scrutiny required of medicines. Or that the authorities would know which devices have harmed patients, how many people have implants and the number of people who are killed by them.

But that's not the case.

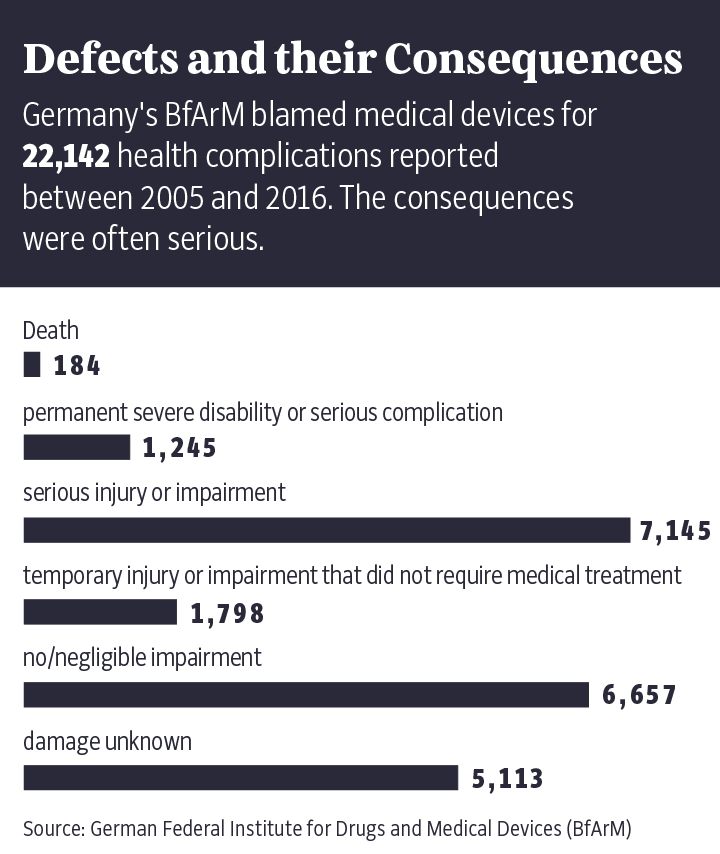

In speaking about the German system for monitoring this lucrative branch of the medical industry, Harald Schweim, the former head of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM), says the system is "very, very bad." And he should know, because the agency he used to run is responsible for oversight of the industry in Germany. That agency will be addressed in greater detail further down.

The

"Implant Files" show that in the U.S. alone, medical devices are

suspected of having caused the deaths of more than 80,000 people in the last

decade. Authorities in the U.S. have collected 500,000 reports in 10 years on

implants that had to be surgically removed because they no longer worked or had

harmed patients.

Still, the U.S. market is better regulated than in Germany. In the European Union, and thus also in Germany, new products often reach the market years earlier than in the U.S. And it's not uncommon for them to fail in field trials involving unsuspecting patients who have placed blind faith in their doctors.

Udo Buchholz was witness to a medical revolution when doctors in Herne implanted a device named Nanostim in his heart around four years ago.

It was the world's smallest pacemaker at the time, no larger than the ink cartridge of a ballpoint pen, and it weighed less than three grams. Even better, it could be implanted without the need for general anesthesia or major surgery. And Buchholz was promised that there would be no complications.

Buchholz could even leave the hospital the day of the procedure, but a few days later, the doctors asked him to return. It was 2014 and Buchholz was one of the first people in Germany to receive one of these new devices, which had been developed by the American company St. Jude Medical. He was asked back to the hospital to speak with local media outlets.

A former tool technician at German carmaker Opel, the 69-year-old Buchholz has salt-and-pepper hair and wears a mustache. He pulls out a newspaper article from back then and says: "What a day that was." A picture shows him smiling into the camera flanked by three doctors. One is the senior surgeon, who praised the pacemaker to the local journalists as the "greatest cardiologic innovation in the last 20 years."

Buchholz, the article noted, could once again live without fear.

Stefanie Preuin

Before doctors implanted Buchholz's Nanostim, the device had only been tested on sheep and on 33 patients. Doctors spent three months monitoring how the pacemaker functioned in those people and in most cases, they reported, there were no problems. In one instance, though, a patient's heart wall was perforated during implantation and he died a few days later of a stroke. On the basis of those tests, Nanostim was released onto the market. The manufacturer did not respond to a request for comment by the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Around three years later, though, an increasing number of problems began cropping up. More and more patients were showing up at hospitals with slowed heart rates and dizziness and doctors realized that the batteries in the Nanostim devices were failing, a development documented in files obtained by the Süddeutsche Zeitung. But the implantation of the devices was also dangerous. In Germany, at least two Nanostim patients died after their pericardium was ruptured during implantation, though it remained unclear whether these deaths were caused by the device or surgeon error.

Either way, Buchholz's pacemaker no longer works, as is the case with Nanostims implanted in several other patients. But because it is extremely risky to take a Nanostim back out again, it's going to stay where it is. In his heart. Four years after his celebrated operation, the showcase patient is now stuck with a piece of scrap metal in his body.

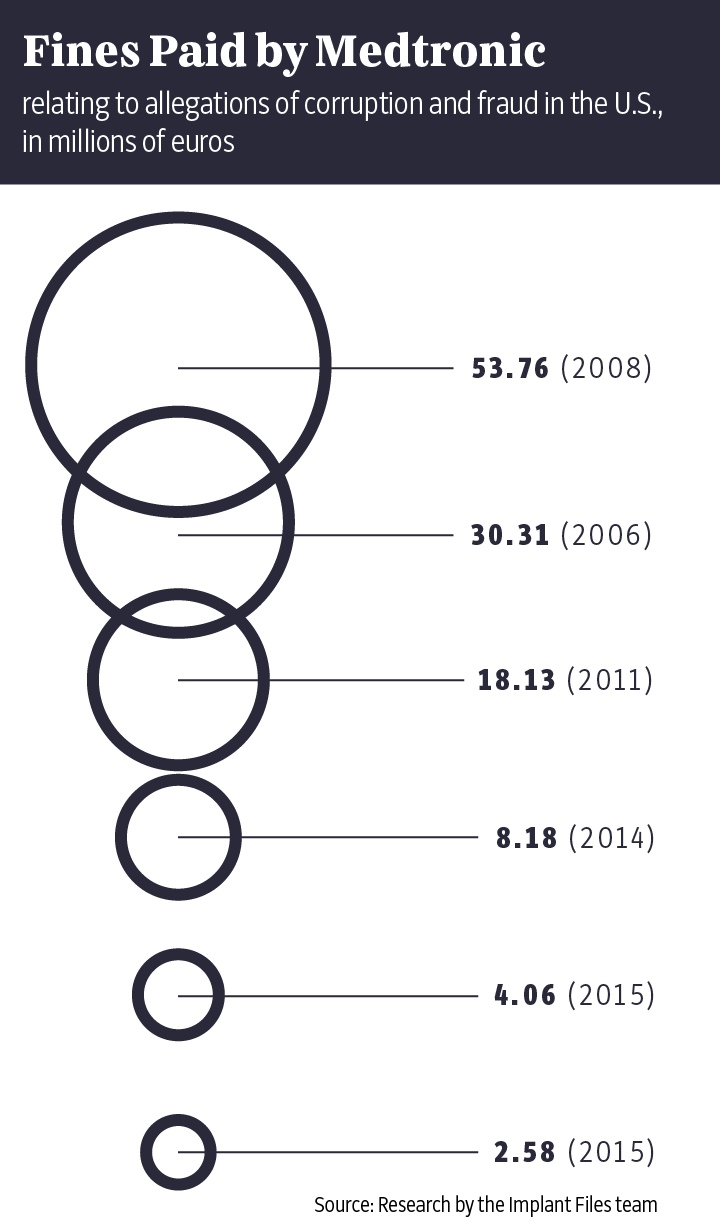

The "Implant Files" show just how often things can go wrong in the poorly regulated medical technology industry. Time and again, doctors insert poorly tested implants or devices into patients like Buchholz without informing them about proven alternatives. The damage done has been enormous. Market leader Medtronic alone has had to set aside $3.2 billion to cover its legal disputes over the past 10 years. In addition, patients often aren't told that the medical devices they are using have already been recalled elsewhere in the world because of life-threatening defects. Meanwhile, the industry and its lobbyists fight fiercely on occasion to prevent stricter controls on the certification of new products.

That's one of the key problems. In Europe, these vital devices aren't tested by public authorities to determine whether they work the way they are supposed to, but by private companies like TÜV and Dekra in Germany or their counterparts in other European Union countries. In officialese, these companies are referred to as "Notified Bodies."

Proponents of this privatized system argue that it accelerates the certification of new products and saves money. Companies frequently demand that governments not disrupt their "innovative strength" through "overregulation," and they reject the idea that the state should take responsibility for inspecting all products. Manufacturers don't want to be required to present extensive studies for every new device, especially if a similar one is already available on the market. And they warn against overwhelming the private testing companies with a slew of new rules, insisting that the resulting delays could cost jobs and even threaten the existence of small- and medium-sized companies in the industry.

But private scrutiny of products also has a downside: Certification companies like TÜV and Dekra have a business relationship with medical device manufacturers. They certify products at the behest of the producers and then bill them for doing so. Governments, meanwhile, look the other way – sometimes at the expense of patients.

How can such a thing be allowed to happen?

Any object that is used in medical examinations or treatment is considered a medical device. They can include everything from tweezers and walkers to X-ray equipment and insulin pumps.

The idea of making improvements to the human body is in no way new. The history of medical devices goes back thousands of years.

The first implantable pacemaker followed in 1958, and the market has exploded since then, just as it has for medicines. Like drugs, medical devices can be both a blessing and a curse. Although they can improve life enormously, they can also cause terrible harm.

That’s why these devices are now divided into risk classes I, II and III, with the third being the "high risk" category. Among the devices included in this class are knee prostheses, pacemakers and breast implants, and such devices can only be sold in Europe if they have obtained the so-called CE Marking. There are around 50 private testing companies in the EU that are permitted to issue that certification. The abbreviation CE stands for Communauté Européenne, the French term for European Community.

"The label isn't a seal of quality for the benefit of the patient, it's a marketing seal," says public health scientist and University of Bremen professor Gerd Glaeske. The testing companies only make money when clients, including major international corporations, come to them.

It is a system that is full of loopholes.

That is how the Nanostim pacemaker, a device in risk class III, was released onto the European market and made its way to Germany. In response to an inquiry from Süddeutsche Zeitung, NDR and WDR, BSI stated that the product had fulfilled all standards applicable at the time. Furthermore, BSI claimed, the company was unaware that a different company had declined to certify Nanostim. Yet the scientific findings were of dubious value from the very beginning. Some of the doctors involved in testing and certifying the device, for example, had received lecturing fees from the manufacturer or were given shares in the company. Employees of the Nanostim producer even participated in one study.

This ultra-permissive certification system means the EU is the weak point in the entire global system. "Products that are harmful can spread across the world very quickly," says Carl Heneghan, a professor of medicine at Oxford. Health officials in countries like South Africa, Mexico and India often look to Europe and the U.S. for guidance.

It's almost as though the certification of medical devices remains stuck in the era when toe prostheses were made of wood and fake teeth carved out of ivory.

In an attempt to gain a better understanding of the chronically opaque medical device market, reporters from 36 countries submitted thousands of inquiries and requested access to government files and statistics, the entire effort coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) in Washington D.C. – the same group that organized reporting into the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers in recent years. The team went through thousands of documents, spoke with hundreds of patients and interviewed experts in the fields of medicine, corruption and consumer protection in an effort to understand the structure and the extent of the problem.

Andreas Rode was still recovering from the aftermath of his spinal surgery at the time the first reports of unforeseen problems began arriving at the headquarters of the artificial disc's manufacturer, Ranier Technology in Cambridge. In 2014, the company issued an urgent safety warning that included the recall of an entire lot number. According to the warning, almost every fifth patient had had to undergo a follow-up operation. Andreas Rode, though, says he initially heard nothing about the warning nor was he informed of the problem reports that accumulated at Germany's Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) in the ensuing years.

The Bonn-based agency should actually be the one charged with protecting patients in Germany. But it has no instruments available to do so. With its around 1,100 employees, the BfArM is little more than a lamentable paper tiger. It is often the manufacturers themselves that end up quietly taking their products off the market, frequently with the justification that demand had dried up. In most cases, they are even responsible for issuing their own product recalls.

When it comes to the certification of new products, by contrast, producers are welcomed with open arms in Europe.

"They did not ask us one question about the safety of our product," Schouten says. "We could just copy data out of the internet."

In the years following his operation, agencies in the Netherlands, Belgium and the United Kingdom all received reports of adverse incidents pertaining to the spinal prosthesis Andreas Rode had implanted in his back. According to documents Süddeutsche Zeitung reporters have seen, the manufacturer didn't even forward on all of the problem reports it had received. When contacted, the former head of Rainer Technology, Geoffrey Andrews, said that the company had never acted in violation of the law according to his knowledge.

The result was that even as new problem cases became known, the prosthesis continued being implanted in more patients. Other patients, meanwhile, missed the opportunity to have their possibly defective artificial discs removed in a timely manner. Andreas Rode's spinal prosthesis had three years to disintegrate into small bits. As a result of all the operations he has undergone, Rode is no longer able to father children. He just got married this year to a woman 13 years his junior and the two of them had hoped to start a family. "But now, that won't happen," he says.

In Germany, government agencies know which car

belongs to whom, how much fuel it consumes on average and when it last

underwent a technical inspection. But when it comes to when and what device

model was implanted in patients' hearts, hips or knees, only doctors and

hospitals are privy to that information.

Stefanie Preuin

Harald Schweim, 68, says the system is "very, very bad." And he knows it well: The pharmacologist was the head of the German government agency BfArM for four years from 2000 to 2004. The fact that private companies examine new devices rather than state agencies? "I think that's wrong." The certification procedure for risky implants? "In my opinion, it should be under state control." The apparent impotence of state authorities? "I have to admit, medical device producers in Germany have an excellent lobby." All the lobbyists have to do is "whistle," he says, and politicians "heel. They're more obedient than my dog."

The BfArM does collect information about problems with medical devices. But in contrast to the U.S., that data is kept confidential. Only select government agencies have access -- but not patients.

The reasons are difficult to understand. In response to a query, the German Health Ministry wrote that a nationwide database was "not prudent" because it is an EU-wide problem. And the BfArM responded by saying that informing the public was "not even partially congruent" with the agency's mission. With that, the curtain is closed, and the questions remain open.

Is it all because of the industry's influence on policymakers? There are four lobbying groups in Germany representing the medical device industry. Years ago, back when he was still the coordinator of health policy for the conservatives in parliament, current German Health Minister Jens Spahn mentioned his numerous meetings with lobbyists. "There are weeks when I have 10 or 20 such discussions," he said. Until 2010, Spahn was even involved himself with the lobbying firm Politas, which advises clients from the fields of medical technology and pharmaceuticals.

Volker Kauder, former floor leader for the CDU

in German parliament and a close confidante of Chancellor Angela Merkel, is

also good at explaining why stricter regulations are apparently undesirable. His

electoral district in southwestern Germany, called Rottweil-Tuttlingen, is home

to a particularly large number of medical device manufacturers.

In a letter to then-Health Minister Hermann Gröhe in November 2014, European parliamentarian Peter Liese (like Gröhe, a member of the CDU) praised himself and his fellow lawmakers from the conservative European People's Party for having blocked an EU law that would have put state agencies in charge of approving medical devices. Back in Berlin, parliamentarians from the parties in government at the time (the CDU, its Bavarian sister party CSU and the business-friendly FDP) sided with the interests of the manufacturers in the 2012 debate over the law, known as the Medical Device Regulation.

Now health minister himself, Jens Spahn has ultimate authority over BfArM. And just how great of an influence his ministry can have over that agency is something that his predecessor Gröhe has already demonstrated. When the Federal Administrative Court ruled in February 2017 that in certain specific cases the BfArM was required to assist seriously ill patients obtain lethal medication for voluntary euthanasia, Gröhe mandated that the state cannot become "a lackey to suicide" – no matter what the court might think. The BfArM got the message, and even today it continues to reject all applications for lethal medications from those wanting to die.

Many victims of defective hip joints, pacemakers or insulin pumps are likewise still hoping in vain for state intervention. The patients want to know why they are suffering, how many of them there are and to whom they can turn to avoid being on the receiving end of another subpar implant. In Germany, patients don't get many answers to such questions because politicians often prioritize the interests of the manufacturers.

This is what such disinformation looks like in

practice:

BfArM

It took a year and a half before the BfArM released documentation in response to a Süddeutsche Zeitung inquiry about just one single case.

BfArM

Some reports about problems with the Nanostim pacemaker were redacted so heavily that they no longer made any sense.

BfArM

Thus far, the BfArM has refused to provide information as to how many dangerous incidents have occurred in the last decade and which products were involved. Such information would help patients learn if their implant has a history of problems.

Neither in the European Union nor globally is there an effective public register or warning system, despite the fact that an average of about 1,000 medical devices are recalled by their producers each year. Reporting by the Implant Files team found that not even one in five countries around the world maintains a database where their citizens can look up safety warnings and find information about medical devices.

As part of the reporting for this series, journalists around the world met with numerous patients who insisted that they had not learned about recalls of the deficient devices implanted in their bodies from the device manufacturers, but from Facebook or self-help networks. Several women in Finland even received implants of one product despite the EU having long-since banned its sale: Essure, a controversial sterilization device from the company Bayer.

Even deaths caused by faulty medical devices are not systematically recorded, nor is the number of people whose lives were put in danger. The result is bizarre inconsistencies in global statistics: Whereas there have been 26,700 recalls of medical devices in the U.S., which has a population of 325 million, in India, with its population of 1.2 billion, there were only 14 such recalls between 2013 and 2017. The collection of data about problems is slipshod, as is the sharing of that information.

Stefanie Preuin

"All of the cases I represent could happen again at any time," says Ruth Schultze-Zeu. The Berlin-based lawyer has represented patients in court for 23 years. In 2015, she won a landmark case before the European Court of Justice that lawyers across Europe can now cite as a precedent: In damage claims, patients no longer have to prove deficiencies with their own devices if a recall or warning has been issued for that device. Without such a recall or warning, however, patients continue to have little to no chance of seeing a lawsuit succeed. "For as long as the system doesn't change, manufacturers basically have a green light to introduce products onto the market with cheap materials or without studies," says Schultze-Zeu.

Even in cases where studies do exist, they are rarely independent. For example, the doctor who implanted a new kind of artificial disc in Andreas Rode's back and who had been involved in its market authorization was financially linked to the manufacturer. When the company went bankrupt, the doctor's name was on the list of creditors. Most studies on medical devices are financed by the industry itself. Studies that don't go well for a producer simply disappear. The process is different when it comes to studies on new drugs. Those must be registered, which makes it more difficult to hide them if the results aren't to the manufacturer's liking.

This approach often makes life even more difficult for patients suffering from faulty devices. They sometimes have to fight for years to prove that their device has a problem, says Schultze-Zeu. One reason it can be difficult to show proof, the lawyer says, is that manufacturers sometimes send their people directly into the operating room when an implant is removed. "They take the implant in the operating room," she says, "even though they are the patient's property" – not to mention evidence in the fight for damage payments. In cases where such damages are actually paid, patients frequently clam up immediately. "Most case are settled out of court and include a non-disclosure agreement," says Schultze-Zeu.

The device in Maria Stirn's chest was supposed to save her life if her heart stopped beating. But on a warm, spring day in 2008, the apparatus started emitting uncontrolled electric shocks: once, twice, three times and more, shock waves coursed through her body. Stirn, whose name has been changed for this story, was pregnant at the time. And she lost her unborn child.

Today, she is not allowed to talk about her case and the involvement of the device's manufacturer Medtronic. She filed a lawsuit against the company after it had expressed its "deep regrets," but refused to pay any damages.

Ultimately, Stirn sent in her unborn child's autopsy report and Medtronic agreed, out of "goodwill," to pay a few thousand euros "indemnification." In return, however, Stirn had to agree to refrain from talking about the case in the future.

For a long time, policymakers merely stood by and did nothing. Starting in 2020, though, a new EU regulation for medical devices should improve the situation, but the roots of the problem will remain: no independent studies; no legally mandated liability insurance for producers; no certainty when a European database for problematic products might be completed and whether the public will have access. If not, the old system will remain in which patients learn of problems entirely by accident, if at all.

The U.S., at least, does have a state agency keeping tabs on the market, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The result is that patients in the EU can receive defective implants that haven't been approved for use in the U.S. and ultimately never will be. One example is the breast implant Trilucent, which thousands of women in Europe received, only for the filling, made of soya oil, to leak out of some of them. Or Robodoc, a robot designed to install hip prosthetics and other devices – and which sometimes injured nerves and ligaments in the process. According to a study in the British Medical Journal, 27 percent of the medical devices first released in Europe were ultimately the target of safety warnings or recalls. For products first released in the U.S., that number was only 14 percent.

"Under the EU system, the public are being used as guinea pigs," Jeffrey Shuren, the head of medical devices for the FDA, said back in 2011. He added: "We don't use our people as guinea pigs in the U.S."

Maria Stirn was 24 years old when she drove her car off the road in 2005. Her heart stopped, but the paramedic was able to revive her. In the hospital, she was told that her heart could stop beating again at any time and she received an implant of a device known as an ICD, half pacemaker, half defibrillator. Included in that implant were Sprint Fidelis leads manufactured by the world's leading producer of medical devices, Medtronic. At the time, they were the thinnest and newest leads on the market.

But these electrodes, which measure the heartbeat and send that information to the pacemaker, produced complications early on. They kept breaking, which would produce a jolt of electricity in the patient. According to FDA data, more than 2,000 deaths can be traced back to Sprint Fidelis leads in the U.S. alone. In October 2007, Medtronic recalled the lead model.

Stirn never got the warning. In spring 2008, her implant gave her several "inadequate ICD shocks," as doctors refer to it. It is considered likely that the death of her unborn baby resulted from those shocks, but it hasn't been proven. Stirn, in any case, had not been promptly informed that the producer had advised patients to speak with their doctors.

How are such oversight and communication failures

possible? Perhaps it has to do with the fact that the medical device industry

has never been involved in the kind of global scandal seen in the

pharmaceuticals industry, where much stricter rules were introduced in the wake

of the thalidomide disaster.

In response to the global outcry, laws pertaining to pharmaceutical products were made more stringent. Since then, producers have had to prove the effectiveness and safety of their drugs in controlled studies. When it comes to medical devices, on the other hand, the only thing that is checked is whether it can do what the producer says it can do. Does an artificial knee bend? Does a defibrillator give off the correct impulse? What isn't tested, however, is how the devices hold up over time in the human body.

Positive consequences can, of course, result from products reaching the market quickly and without myriad bureaucratic hurdles. It is sometimes the case that patients are waiting impatiently for new devices that promise new ways of treating what ails them. As such, the decisions made by the private certification companies don't just stand between companies and their profits, but also sometimes between patients and their recoveries. But that is also true of the pharmaceutical industry, and there is nevertheless unanimity in the medical field that strict rules for the approval of new drugs are necessary.

The companies that provide certification to medical devices, by contrast, are often content to merely flip through a stack of papers. This was the pattern followed in the certification of reporter Jet Schouten's mandarin net as "vaginal mesh."

Her experiment worked because of the so-called "substantial equivalence" principle. It holds that certification is allowed without clinical studies or tests if a similar product is already on the market that was, at some point, tested on people. As a consequence, new medical products can be sold without ever having been tested on actual patients.

Using the example of a hip prosthesis made by the medical device manufacturer Johnson & Johnson, scientists have demonstrated the absurdities that the substantial equivalence principle can produce.

To avoid having to carry out any clinical studies of its own, the company pointed to similarities with six other implants that were already on the market. Those implants, though, had been certified in the same way. Indirectly, Johnson & Johnson was basing its certification application on 63 that had come before. Some of them were more than 30 years old and had long since been taken out of circulation because of frequent complications.

A spokesperson for Johnson & Johnson said that most medical devices are brought onto the market according to this procedure. The safety and efficiency of all products, he noted, are independently tested by the responsible U.S. authority, the FDA.

Substantial equivalence also explains why some 10,000 medical devices have been introduced to the market in the last eight years, while fewer than 100 have been rejected.

Which ones? Neither government agencies nor the testing companies are willing to release the names of the products in question or their manufacturers. In response to a request for comment from the Süddeutsche Zeitung, the German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information – like the BfArM, an agency that answers to the German Health Ministry – wrote that lawmakers are "deliberately" unwilling to make the data "available to the public at large."

Deliberately withholding information from German citizens? But why?

One might think that Health Minister Jens Spahn would have a fair amount to say about the subject. But over the course of two months, he was unable to find the time for an interview. His ministry instructed that written questions be submitted, and his spokesperson elaborated: Please limit the list to "the important questions."

The minister apparently has other priorities. When a Süddeutsche Zeitung reporter asked him on the sidelines of a gala why people in Germany should not be allowed to learn about the problems associated with medical devices, he seemed surprised – as though the issue, and the media's interest in it, was completely new to him.

How must that look to people like Andreas Rode, Maria Stirn and Udo Buchholz?

The spinal prosthesis that was implanted in Andreas Rode's back as part of a study, and which later apparently disintegrated inside his body, was approved for the European market just a few months after his operation and implanted in more than 100 patients in the hospital in the Lower-Saxony town of Leer alone. Around 70 of them had to have follow-up surgery to remove the implants. The spine surgeon responsible has since been indicted for bodily injury. But Rode and the patients from Leer can no longer take legal action against the producer of the artificial disc. The company went bankrupt in October 2015.

As for Maria Stirn, who lost her unborn child, it remains impossible to find out how she is doing today. The non-disclosure agreement she signed as part of her settlement with Medtronic still prevents her from speaking about the tragedy.

In May 2017, Udo Buchholz wrote an email to St. Jude Medical, the manufacturer of his Nanostim pacemaker. He had been promised that the device had a lifespan of 10 years. "But now, the battery has prematurely expired. Will my Nanostim be replaced?" Buchholz asked. He still hasn't received a reply.

By Christina Berndt, Katrin Langhans, Mauritius Much, Frederik Obermaier, Bastian Obermayer, Anna Reuß, Nicolas Richter and Ralf Wiegand