When the police called Raphaël Halet, he was at the doctor's office; his back was acting up again. On the phone, a French official informed Halet that someone had broken into his home and stolen one of his cars. Could he please come immediately? Halet took off at once, never even thinking it might be a trap.

When he arrived at his house in the tiny village of Viviers in France's Lorraine region, there were several people waiting for him, including two police officers, a bailiff, a locksmith, a computer specialist and a representative of his employer, the Luxembourg branch of the international consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). There hadn't been a break-in, nor had one of his cars been stolen; that had all been just a story to lure Halet back home. Once there, he was presented with a five-page warrant that had been issued the day before by a judge in Metz, France. It was a remarkable document. In it, the French government had taken the side of a billion-euro multinational corporation keen on finding and punishing a whistleblower within its ranks.

Raphaël Halet was that whistleblower, and the documents he leaked to a journalist formed the basis for the Luxembourg Leaks scandal that broke a few weeks before the house raid in Viviers. A consortium of European media, including the Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), analyzed the internal documents and published them in late 2014. Thanks to Halet, it was revealed that PwC had been a key accomplice in helping corporations avoid millions of euros in taxes by way of Luxembourg – with some of the methods used later being found illegal. PwC, for its part, claimed that it had always acted in accordance with the law. The scandal itself damaged Luxembourg's reputation as a financial hub and carried some political backlash for the country's former prime minister, Jean-Claude Juncker, who had just been elected president of the European Commission. Juncker is regarded as one of the architects of Luxembourg's tax avoidance scheme. But there was one party that didn't feel any backlash whatsoever: PwC.

In the search warrant, the judge had permitted investigators to copy Halet's emails, "including any email, and any part and attachment, addressed to or received from a journalist." Halet later told journalists at a meeting in Metz that the bailiff and the PwC representative had summoned him into his office, where they had him turn on his computer and sign into his email. The investigators were looking for emails to or from a single person: Edouard Perrin, a French investigative journalist. And they found what they were looking for: The whistleblower and the journalist were taken to court.

All this occured at the behest of a corporation with which most people are largely unfamiliar. Whether by its acronym, PwC, or its full name, PricewaterhouseCoopers, the consulting firm doesn't offer any services that ordinary people would buy or use and many people know nothing about it, even though PwC has hundreds of branches around the world, 21 of them in Germany alone. Even people who have heard of PwC probably couldn't say exactly what the company does. Which is why most people aren't particularly concerned about it.

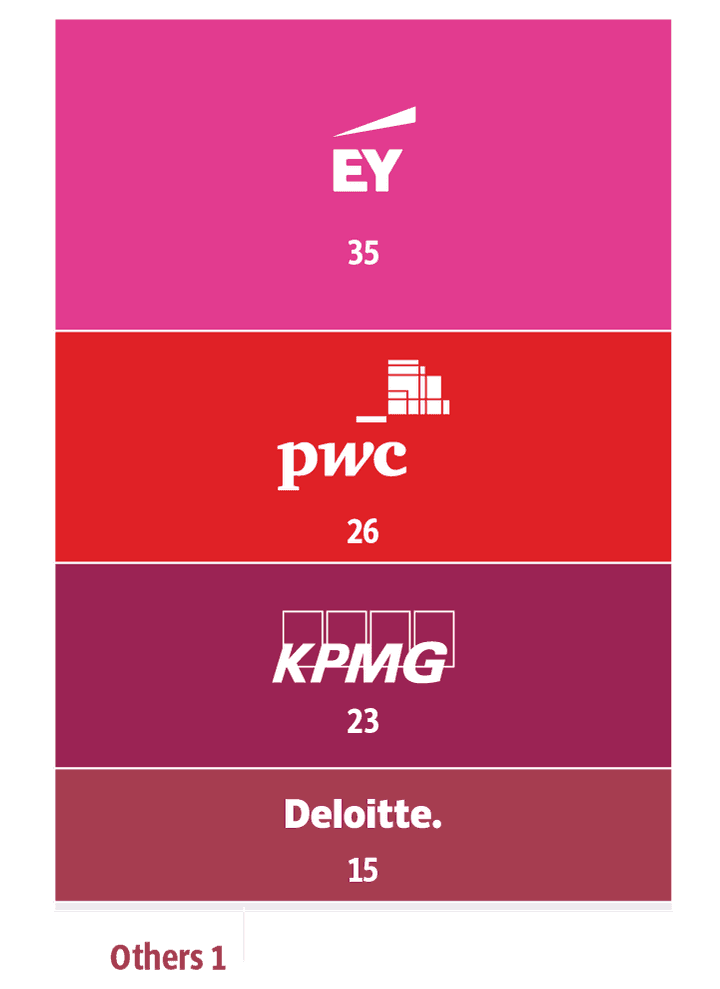

But they probably should be, as joint reporting by the SZ and the two German broadcasters NDR and WDR has shown. PwC is one of the most powerful companies in the world, especially when it's in lockstep with the other three big global consulting and auditing firms, KPMG, EY (formerly known as Ernst & Young) and Deloitte. Known together as the "Big Four," this quartet of companies generally flies under the radar of public awareness. They are faceless, but together they represent a sinister power with a global reach.

Even if clients get punished, their quiet accomplices escape unscathed

In recent years, these four companies have repeatedly played key roles in a spate of major scandals, including some that have been investigated by the SZ, such as the Luxembourg Leaks and the Panama Papers. But even when the Big Four were accessories to partly illegal or at least illegitimate acts, they have always managed to walk away unscathed. Even when their clients are publicly denounced or pilloried, hardly anything ever sticks to the Big Four. One of the most internationally renowned experts on the Big Four is also one of their loudest critics: the British economics professor Prem Sikka. Rather than using the term Big Four, he refers to them as "the pinstripe mafia."

Its an evening in autumn 2018 and Sikka is just leaving PwC's London headquarters near the Embankment tube station. The building is an imposing structure of concrete and marble that sits on the bank of the River Thames. In Britain, the operations of the Big Four are more widely debated than they are in Germany – which is part of the reason the Labour Party commissioned Sikka to conduct a study on possible reforms of the Big Four. Indeed, that is the reason for Sikka's visit to PwC headquarters this evening. The visit, though, wasn't overly pleasant for either party, according to Sikka's account. The professor makes a point of referring to the Big Four by the pejorative nickname "pinstripe mafia" and he openly argues that they present a danger to democracy. "This mafia doesn't shoot people, but its activities are just as deadly," he wrote in a journal article several yeas ago. "They deprive millions of jobs, education, savings, pensions, security, food, healthcare, clean water and social infrastructure."

These are serious accusations. To understand them it is first necessary to explain what it is the Big Four actually do: PwC, KPMG, Ernst & Young and Deloitte offer consulting services to large corporations, banks and the super-rich in more than 180 countries. Together they have more than a million employees who advise clients on matters pertaining to tax structures, business strategy and a wide variety of other fields. Sometimes they prescribe sweeping restructuring, at others a reorientation, and at still others, they develop tax avoidance models. The Big Four earn the vast majority of their income through consulting fees.

In addition, the Big Four audit financial statements and balance sheets on behalf of their clients. These audit reports are presented to supervisory boards, investors and authorities and are supposed to show a company's financial health and indicate where improvements can be made. The Big Four have divided the international auditing market amongst themselves, at least when it comes to the largest companies; 99 of of the 100 companies listed on the Nasdaq 100 stock market index are Big Four clients.

Possessing such market leverage can be seductive. In Australia, authorities are investigating whether the Big Four engaged in illegal price fixing over public tenders. In Italy, KPMG, Deloitte, PwC and EY have been forced to pay more than 23 million euros ($26.2 million) on cartel charges. Yet viewed against the Big Four's global turnover – around 120 billion euros – such fines are a mere pittance.

How the Big Four operate and what they advise their clients is rarely made public and considered to be trade secrets. Unless, that is, a person like Raphaël Halet reveals them. What he and a second whistleblower named Antoine Deltour brought to light in 2014 threatened to drag the work of the consultancy firms into the spotlight. Such as how these financial wizards move euros and dollars around the world, over and over again, until their clients' tax burdens are reduced to virtually nothing.

That likely explains why PwC didn't only go after the whistleblower, but also the investigative journalist who received the documents. But they weren't successful in the end. After more than three years of hearings, Luxembourg's highest court ruled that Halet only had to pay a fine of 1,000 euros while Deltour was acquitted altogether. So, too, was the journalist Perrin a few months prior.

It wasn't only PwC that used Luxembourg as a tax haven. Documents from Deloitte, KPMG and Ernst & Young also made up part of Luxembourg Leaks, and these companies, too, helped their clients minimize their tax burdens. The furniture giant IKEA, for instance, was able to lower its tax bill to less than 0.002 percent. When the scandal came to light, however, attention wasn't focused on PwC, but rather on the actual tax avoiders it had assisted. In addition to IKEA, Amazon, Deutsche Bank, E.ON, Pepsi and Starbucks, as well as other companies, were criticized and some were even faced with boycotts. Their consultants, on the other hand, managed to remain almost entirely out of the line of fire.

One of the foremost experts in the offshore world is the British journalist Nicholas Shaxson. He once said: "The Big Four have done more than any other group to sustain the global system of offshore tax havens." Through this system of letterbox firms and legal skulduggery, billions and billions of dollars in tax debts are erased from companies' books year after year, harming millions of people around the globe.

But for the Big Four, it's worth it. In the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers and Offshore Leaks alone, there were around 100,000 mentions of the Big Four. Yet in articles and TV reports, their names only appear sporadically. The media, including the SZ, have so far mostly focused on their clients, i.e. the beneficiaries of tax avoidance or tax evasion, rather than on the architects of those schemes.

KPMG claims not to have noticed inconsistencies inside FIFA

It's astonishing how many scandals there have been in which one of the Big Four has played a role. For years, KPMG kept an eye on FIFA's books, but in all that time, their experts supposedly never noticed that the acolytes surrounding FIFA head Joseph Blatter were routinely taking payouts. Shortly before the global financial crisis broke out in 2008, EY (which was working for Lehman Brothers), Deloitte (Bear Stearns) and PwC (insurance giant AIG) were far too late in identifying catastrophic problems with their clients' balance sheets. In Germany, experts say KPMG was delinquent in its audit of Hypo Real Estate, the real estate financier that ultimately had to be nationalized, and that PwC likewise failed in its audit of the Saxon state bank, the Sächsische Landesbank, which had to be shut down. As the empire of the film mogul Leo Kirch began to collapse, KPMG saw no cause for concern until the very end. And then there's the Cum-Ex scandal, perhaps the biggest tax theft in European history. Thanks to the banks' tax tricks, public coffers may have been deprived of as much as 5.7 billion euros. And who was checking the banks' financial statements? Ernst & Young, KPMG, PwC and Deloitte.

But in the end, nothing sticks to the Big Four. It helps that while they each have headquarters – KPMG in Zug, the Swiss tax haven, and the others in London – they also have decentralized organizational structures. This allows each of them to limit liability and damage claims. When it comes to their own operations, a sense of global responsibility doesn't play much of a role.

The SZ requested interviews with all four companies, but was rebuffed by each one. Instead, KPMG, EY, Deloitte and PwC provided boilerplate answers to specific questions.

KPMG, for example, stated that it "ensures compliance with all professional and regulatory standards and regulations."

PwC said it provided services "in the best quality possible."

Deloitte's statement said that it "always works within the framework of legal requirements and applicable law."

And EY stressed the importance of ensuring security and transparency in order to make an "important contribution to the function of the capital and credit markets."

None of their statements actually say much at all. Indeed, transparency doesn't seem to be a forte of any of the Big Four – rather ironic, considering their profession was originally created to prevent fraud.

From the "Big Eight" to the "Big Four"

The origins of the Big Four can be traced back to England and 19th-century America, in the era of big railway projects. Back then, the world of finance was about as regulated as the Wild West, with scammers regularly enriching themselves with investors' money. British parliament decided that the books of companies traded on the stock exchange should be audited. To do this, though, specialists were needed – and so the auditing profession was born. The principle that these people must be independent has been widely accepted around the world; in Germany, it's enshrined in law.

The down side of auditing is that it takes place at the end of the year, when companies crunch numbers for their balance sheets and the auditors compile what then gets shown to investors. During the rest of the year, though, it was hard for these auditing firms to keep their expensive staffs busy. So they began offering consulting services, especially in matters of taxation, essentially leveraging the fact that they already had intimate knowledge of the companies from auditing. And consulting became increasingly lucrative: For several years, the Big Four has been bringing in more money through consulting fees than auditing.

By the middle of the last century, the number of consulting firms had been whittled down, with the "Big Eight" becoming the "Big Five." When Arthur Andersen was brought down after the Enron scandal of 2002, only the Big Four remained. Though it seems fair to ask whether the four survivors haven't perhaps also failed in their auditing duties one time too many. Or why auditors, who themselves have come into conflict with the law time and again, should be the ones to verify whether other companies are being honest. But hardly anyone's asking such questions. The Big Four are omnipresent, as much a hallmark of the globalized economy as quarterly figures, shareholder meetings and executive organigrams. They cooperate with professors at German universities and they are a fixture at the World Economic Forum in Davos, just as they are at the SZ's Economic Summit in Berlin.

The catch-22 is obvious: Auditors are supposed to scrutinize their clients' books, but they also want to be hired again the next year. On top of that, they want companies to take advantage of their consulting services as well, which creates dependency and a lack of professional remove. What if an auditor finds something that could not only prove bothersome to a client, but aso ruin them? A young auditor from Ernst & Young faced this exact problem back in 2006 as he combed through the balance sheets of a U.S. investment bank. He discovered an accounting trick the bank was using to hide its excessive debt load. The employee wrote an email to his superiors at Ernst & Young, warning them of a "reputational risk." He wanted to know whether the practice was in line with "regulatory guidance." His reservations apparently weren't taken seriously enough, for the accounting trick ultimately led to the client's demise. The bank was Lehman Brothers; it collapsed two years later.

The global economy followed the bank into the abyss. At the time, Lehman Brothers had around $50 billion in debt hidden in its books, according to an investigation report. Ernst & Young, however, claims that its audit of the bank found that Lehman's financial statements were "in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles."

The Big Four often push the limit of legality

This episode fits into the picture of the Big Four outlined by Sikka, the economics professor. The catalyst of his current study was the billion-dollar collapse of Britain's second-largest construction firm, Carillion, a company with more than 40,000 employees. All of the Big Four had been working for Carillion, and yet none of them had warned against its impending collapse. A cross-party committee of the British parliament later concluded that KPMG, EY, PwC and Deloitte needed to be reformed or even broken up. The committee's chairman said: "It is a parasitical relationship, which sees the auditors prosper, regardless of what happens to the companies, employees and investors who rely on their scrutiny."

It's this impunity that Prem Sikka wants to end. As the professor sits in front of a slice of pizza and a Diet Coke, he explains his concern: "If you poison yourself with pizza or get sick from it, the restaurant owner will be punished for it," says Sikka, "but if an audit is false and not worth the paper on which it is written it, then that's not a problem. That can't be right." And that's only half the problem. The other half are the tax tricks that PwC, Deloitte, et al. develop for their clients. This, Sikka explains, is how the Big Four effectively plunder state coffers – to the detriment of ordinary citizens, because that money does not then go to hospitals, schools and infrastructure.

A 38-page strategy paper prepared by Deloitte for the hotel chain Meininger, which was leaked to the SZ as part of the Paradise Papers, provides a perfect example. The core of Deloitte's proposal is that Meininger should rent a basement space on the Isle of Man for 7,000 euros which the hotel chain only had to use five times a year. Combine that with an investment company headquartered in the same basement, plus an internal loan of nearly 135 million euros and a profit transfer, and the structure apparently enabled Meininger to save a huge amount on taxes.

When it comes to tax consultancy, the Big Four are often right on the line of what is legal and what is not. So they're careful. Every sensitive presentation to clients, every piece of paper, every document is a potential source of trouble. That's why KPMG client presentations are sometimes only given on whiteboards – so they can be erased afterward. In one internal email, cited by U.S. investigators in a 2007 indictment, Ernst & Young said there "should be no materials in the clients‘ hands – or even in their memory." A single fax to the government, it added, could have "calamitous results."

It's a business model based on risk analysis of legal gray areas. The calculus: How much money can we and our clients earn with a certain tax scheme? What if we're caught? One British manager realized his colleagues were recommending tax tricks to clients even if there was only a 25 percent likelihood they wouldn't run afoul with the law. One KPMG paper, made public in 2003, said something similar, namely that the fines would be "no greater than $14,000 per $100,000 in KPMG fees."

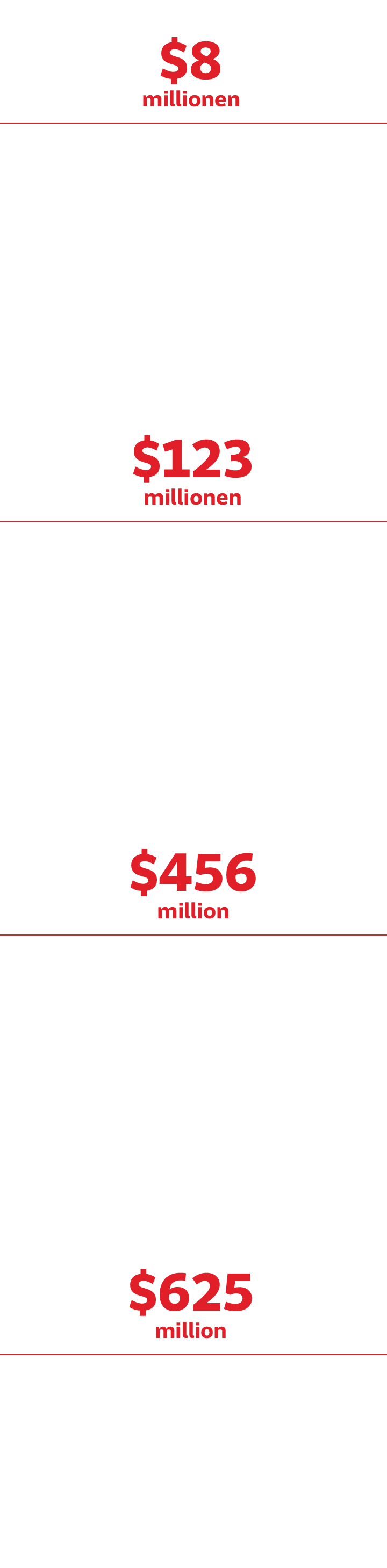

But sometimes, the penalties likely did exceed the companies' revenues:

KPMG was forced to pay $456 million in 2005 because they had, among other things, developed illegal tax models for customers of Deutsche Bank. The bank had to pay $550 million as well – a hefty fine even for a financial institution that is no stranger to scandals. What's more: The company that has been auditing Deutsche Bank's books since 1952? KPMG. And if the auditors ever found any inconsistencies, they sure didn't tell anyone.

The Know-How Monopoly

It is a prime example of a conflict of interest: an auditor doubling as a consultant. KPMG should have been the one warning Deutsche Bank's shareholders that the bank was aiding and abetting tax evasion, that its reputation was under enormous threat and that it faced potentially horrendous fines. But KPMG was also the one who came up with the tax model in the first place. As far as Deutsche Bank is concerned, even the German financial supervisory authority has lost its patience with the lender. It has tapped special auditors to ensure Deutsche Bank gets its money laundering problem under control. It might sound like a good idea, except for one salient fact: The special auditors are from KPMG.

The power of the Big Four goes even further, reaching beyond the economy and deep into the world of politics. The Big Four's client list includes countries, governments and public agencies. The same Big Four that help deprive public coffers of millions of euros each year by instructing their clients how to avoid paying taxes are also handed millions of euros in government contracts, as recently reported in German media outlets Der Spiegel and Bild. Between 2007 and 2017, the German Finance Ministry awarded PwC auditing and consulting contracts worth 30 million euros a year. In 2017, nine of Germany's 14 ministries awarded contracts to the Big Four.

Among the services provided was an assessment of Air Berlin's financial standing, which served as the basis for a 150 million-euro credit guarantee from the German government, a short-term loan that still hasn't been fully paid back after the airline's 2017 bankruptcy. PwC also conducted the risk assessment.

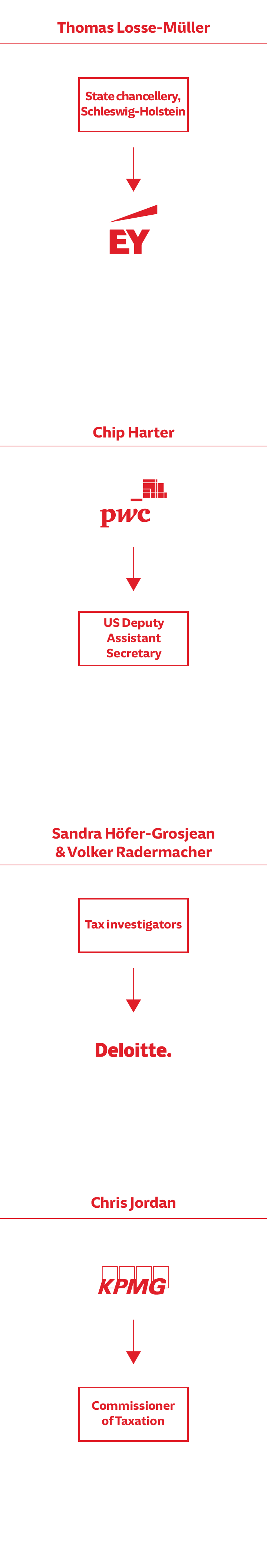

Like myriad companies, many public agencies are also dependent on the Big Four. One former Big Four partner told the Financial Times a few years ago that government and consulting firms were locked in a "Faustian relationship." This deal with the devil looks something like this: The more often governments call in consultants due to their own lack of specialized knowledge, the less specialized knowledge is developed within the government itself – and the more consultants need to be called in. And the consultants, it should be noted, aren't necessarily neutral: It is far from clear whether they'll use the insider knowledge they glean from within the government for other purposes. Indeed, employees of the Big Four may be involved in drafting laws, for instance, or they might exert influence in other key areas – and they do so without any democratic legitimation.

At the same time, the Big Four lure particularly knowledgeable officials with lucrative offers, leading to what experts refer to as a "know-how monopoly." The imbalance is only growing as the Big Four continue their spending spree. Furthermore, it's not just ministries – where draft laws are often formulated – that are affected, but also the agencies that must implement the laws once they are passed. In 2018, for instance, two of Germany's most renowned tax investigators left public service to join Deloitte – despite the fact that tax investigators have long complained of being vastly outnumbered by specialized consultants when they visit a company to audit its books. Now, they must even face former colleagues across the table from them.

Gerhard Schick is one of the few financial experts German who focuses on the Big Four. A member of the Green Party, he resigned from German parliament in order to fully dedicate himself to the cause of reforming the international financial system. Schick says the investigative committee that looked into the bankruptcy of the Munich-based lender Hypo Real Estate also discussed the failures of the auditors, as they did when looking into the Cum-Ex scandal as well. He calls for Germany's financial supervisory authority "to build up its own staff to go to the banks instead of just sending the auditors." In the U.S., he notes, that approach has long since become standard.

There are, in other words, ideas for reining in the Big Four. One option could be to simply deny them government contracts as long as they help their clients avoid paying taxes. Another would be to make them liable for damages caused by deficient audits. Michael Gschrei, the chairman of an association of mid-sized auditors, is in favor of a so-called "joint audit," as is the practice in France. There, two different auditing companies check the books of one single company. Because they work independently of one another, each acts as a backstop for the other's work. The British professor Richard Murphy calls for the strict separation of auditing and consulting. The Big Four's claims that they are capable of doing both and still steering clear of any conflict of interest is, for Murphy, "absolutely absurd."

All of these are sensible suggestions. It's also not as if regulations governing the activities of the Big Four have never been attempted. In 2011, two years after the financial crisis, EU Internal Market Commissioner Michel Barnier submitted a draft law to do just that. The Big Four were incensed. One KPMG partner turned to the responsible division head at the German Justice Ministry and said that the Commission's suggestion had "caused quite a stir." What followed were meetings and emails with Big Four representatives, lobbyists and lobby umbrella organizations. In the end, the passage holding the Big Four jointly responsible for the financial crisis was removed from Barnier's draft. Another passage that disappeared stated that consulting firms should not be permitted to audit companies in which they have a business or financial interest. The part about separating auditing and consulting was also watered down: Instead of an outright ban, there was merely a requirement that an auditing committee approve each individual case and – absurdly – get assurances from the auditing companies themselves that their independence was not compromised.

And so, the Big Four's lobbyists have been able to keep business and politics within their control. Their auditing monopoly and their "know-how" monopoly will continue to grow as long as governments don't step in. And yet, if one or two of the Big Four were to be shut down – say, for dereliction or criminal activity – this could cause a whole new global problem: There's no one to pick up the slack the companies would leave behind. The fifth-, sixth-, seventh- and eighth-largest auditing companies combined are as large as the smallest of the Big Four. The British journalist Richard Brooks sums it up nicely: The Big Four are "too few to fail."