Zaida Catalán is sitting in the dust, surrounded by armed men somewhere in Kasaï-Central, a province in southern Congo. Zaida's colleague Michael Sharp is sitting across from her. Both are barefoot and have nothing with them aside from the clothes on their backs. I have children, says Zaida, "Moi, j'ai des enfants." But it's not true. It's the kind of thing you say when the only thing left to hope for is mercy.

That same Sunday afternoon in March 2017, a young teacher named Elizabeth Morseby is visiting her mother Maria on Öland, a Swedish island in the Baltic Sea. The two chat in the kitchen as the food simmers on the stove. At 3:49 p.m., Elizabeth's phone rings. The display shows the name of her sister, Zaida Catalán, and her Congolese mobile phone number.

Zaida hasn't been in touch from Congo in weeks. When they don't hear from her, her mother and sister assume it means that everything is just fine.

Now, they're hearing from her.

Only it's not Zaida's voice on the other end of the line, but those of men, a bewildering number of them. They're all speaking over each other in a language the two women don't understand. Elizabeth has put the call on loudspeaker and the men's voices from Congo fill the kitchen in Sweden. "Hello," Elizabeth and her mother say over and over again. "Hello Zaida, are you there?" Maybe she's in a café, they think at first, maybe she hit the dial button by accident.

Along with the men's voices, they can also hear breathing close to the microphone. After one minute and 12 seconds, the call ends. They try calling back seven times before then dialing the number of Zaida's colleague Michael, but no one picks up. Zaida and Michael are in the contested region in southern Congo on behalf of the United Nations Security Council.

Maria Morseby sits down at her computer and writes an e-mail to UN headquarters in New York describing the strange call she received. "I am deeply concerned something has happened to my daughter Zaida Catalán," she writes. At 9:35 p.m. that same evening, she receives a reply. “We wanted to acknowledge receipt of your message and to let you know that relevant security protocols have been activated to get in contact with Zaida."

Maria Morseby is anything but reassured, but she is confident that she can fully trust the UN. That trust, though, will soon be severely shaken.

Maria and Elizabeth Morseby wait for a sign of life from Zaida and call Michael Sharp's parents in the U.S. They establish a WhatsApp group where they share the latest news from Congo in addition to their thoughts, hopes and potential scenarios for what might have happened. They wonder whether the two might have been kidnapped and if a demand for ransom may be coming soon. The families also pray together over the phone.

After two weeks, Maria Morseby's doorbell rings in the middle of the night. It's the Swedish police, who have come to deliver the message that Maria has been fearing the most. On March 27, UN soldiers from Uruguay found the hastily buried bodies of two Caucasians, a man and a woman. The head was missing from the female body, but they were able to identify Catalán by the small tattoo on her right wrist, which read: "Per aspera ad astra." Through hardship to the stars, a Latin quote from a tragedy written by the Roman dramatist Seneca the Younger.

The unspeakable has befallen Maria Morseby. She clings to the belief that the United Nations will do everything it can to investigate her daughter's death. She receives letters from diplomats from a number of UN member states in addition to one from UN Secretary General António Guterres, in which he writes:

"Please rest assured that the UN remains deeply committed to ensuring that those responsible for the deaths of Zaida Catalán and Michael Sharp are brought to justice."

Looking back, Maria Morseby says the letters were written with "incredible warmth." At the time, she had no idea that the investigation into her daughter's death would get caught up in the wheels of global diplomacy.

Zaida Catalán's mother is a Swedish environmental activist, her father a Chilean dissident. "As a six-year-old, she actually asked me: 'Mama, what can I do to make the world a better world for everyone to live in?'" says Maria Morseby, a woman with wild, silver-colored hair and eyes ringed with black eyeliner. "I told her: You could, for example, study law later. Then you could become a lawyer or change the laws of a country."

Zaida Catalán would indeed go on to study law and become the president of the youth wing of Sweden's Green Party. She was an activist for women's rights and fought against the meat industry. Some thought that Zaida had a promising gift for politics, but everything went too slowly for her in politics, with too much talking and too little action. She wanted to do something more tangible, so she traveled to Congo for the European Union and to Afghanistan on behalf of the UN. Was she perhaps a little overconfident, or even reckless, as some media reports suggested after her death?

Maria Morseby sneers derisively. "Kasaï was her fourth mission," she says. "She had undergone all kinds of security training, including for kidnapping. But she also knew that if she wanted to talk to women who had been raped by militias or whose children had been killed, she couldn't show up with a bunch of armed men."

Did she have herself to blame? Was she too careless? On April 24, Congolese Information Minister Lambert Mende addresses journalists, but it is no ordinary press conference. A short film is projected onto the wall, a shaky mobile phone video that is six minutes and 17 seconds long. It shows Catalán and Sharp walking through an arid landscape.

Seconds later, a shot rings out and Sharp crumples to the ground. Catalán jumps up, and she is shot down as well.

More shots are fired before one of the young men steps toward her body and begins sawing away at her neck with a machete. It takes about two minutes before the head is completely detached.

"Here you see how the men of Kamwina Nsapu act," the minister says after screening the video to stunned journalists. What they have just seen, he says, is "the work of terrorists who must be eliminated by all means necessary."

Afterward, the video begins circulating on the internet, and Zaida Catalán's mother and sister resolve to watch it together. "I wanted to know what happened to her," says Maria Morseby. "I wanted to be with her. My beloved daughter. I would have been happy to change places with her. I wanted to protect her, but I couldn't. I couldn't help her."

The Swedish government lodges a protest with the Congolese and demands answers, as do others: How could they possibly have decided to show a video like that in public? The Congolese government, though, defends its decision, with the Congolese president's chief diplomatic adviser, Barneby Kikaya Bin Karubi, saying: "The UN were not happy that we released it, but we had to do it because everyone was saying the government was responsible." The red headbands, the chants of "Long live Kamwina Nsapu" during the decapitation: all of that, the adviser notes, removes all doubts about who was truly behind the murder.

Sonia Rolley, a reporter with the French international broadcaster RFI, was traveling in Kasaï at the same time as the two UN experts and met with them in their hotel the morning of their disappearance. "I have collected many videos of executions in Kasaï," she says, "but none look like this one. This is doubtlessly a completely different story."

Rolley has transcribed the video with the help of native speakers – each spoken word in the respective language. "Speak gently to them, or they may try to run away, don't stress them out," one of the men says at the beginning of the video in Ciluba, the language spoken in Kasaï and the native language of the Kamwina Nsapu rebels. The sentence, "Have them sit down," is also in Ciluba. But then comes the order to open fire: "Tirez! Tirez lisusu!" Fire, fire again. The leader suddenly begins issuing commands in Lingala, a national language of the Congo spoken in the government and the army. It is a language the Kamwina Nsapu people regard as a "language for pigs." Furthermore, two of the men in the video speak rather broken Ciluba; the language of the Kamwina Nsapu obviously isn't their mother tongue.

Is it possible the leaders of the death squad came from somewhere else?

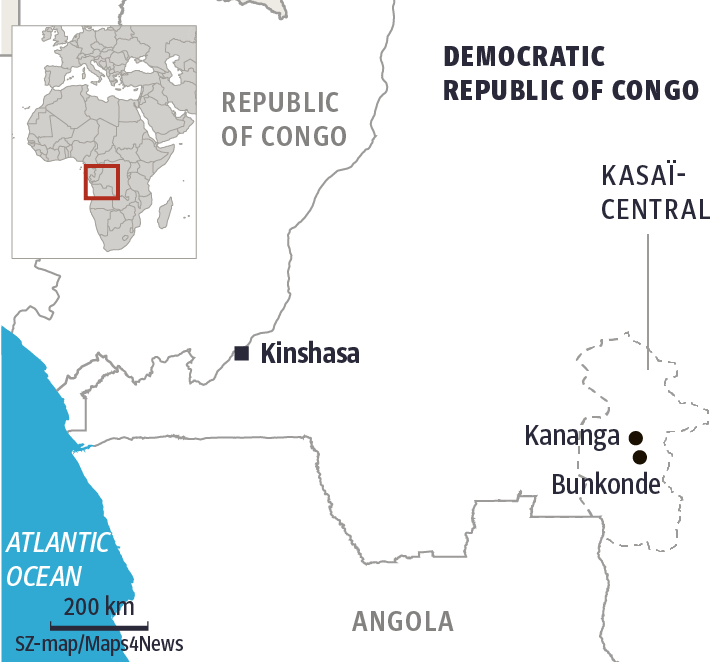

The suspicion is reinforced by another audio document. The day before their death, Catalán and Sharp sat together at the Wood Land hotel in Kananga, the provincial capital of Kasaï-Central, to plan their research trip. With them at the table was a certain François Mwamba, who was introduced as the "Father of Kamwina Nsapu".

Catalán secretly recorded the conversation, which lasted just over an hour, with her phone. In the conversation, she and Sharp introduce themselves and say that they will be sending their report to the UN Security Council. They explain they have already spoken with authorities, with police and army officials and that, now, they want to speak with the Kamwina Nsapu "family," and also to militia fighters. They say they want "to listen to every actor in the crisis."

They also want to know from the rebel leader whether it is safe to go to Bunkonde, one of the militia's strongholds. He says several times in his mother tongue Ciluba to others at the table, who then translate the conversation into French, that they should not lure the UN experts to areas over which he has no control. "Be careful and don't get them into trouble," he says. At the most, he says, they should only provide guarantees about the militias in their own villages, because he doesn't have control over the others. "Don't talk about the ones in Bunkonde."

He repeats his warnings several times, and toward the end of the conversation, he says very clearly one more time: "We have to be cautious when we speak to them. You might give them guarantees only to have them drive off and get ambushed. Then afterwards, they'll say: They gave us guarantees."

One of the men, though, passed on the words of the "elder" a bit differently: "The situation in Bunkonde is different than it is where we are. But as for the guarantees: You can come to Bunkonde, nothing will happen there, nothing will happen." As if to be absolutely sure the two wouldn't try to back out and not go, he says: "They won't do anything. You'll get through without any problems."

Catalán and Sharp thank them. "OK, we're ready to head out tomorrow," says Sharp, "to Bunkonde and to the places where you can see the militias."

The two UN experts were apparently lured into a trap. Presumably by men who have close ties to the Congolese intelligence service and the army.

Telephone records obtained by the Süddeutsche Zeitung and analyzed together with international colleagues show that the translator, who would also accompany the two UN experts on their deadly trip the next day, made regular calls to a colonel with the Congolese army during that period. Each time after the two UN experts called him, he then called the military officer.

Also on the list of phone calls is a cousin of the translator, who organized the three motorcycle drivers for the trip. This cousin is known to have been an informant for the state intelligence service in the past, a fact which he would later admit to in court. The phone records also include calls to a teacher from the region who would become the first witness to report the death of two Caucasians who had been killed by Kamwina Nsapu. The teacher made calls to several journalists and politicians, the first one being made just 26 minutes after the last sign of life from Zaida Catalán – the call to the mobile phone of her sister in Sweden. In the trial focusing on the death of the two UN experts, held in a military court, the man was initially listed as the key witness. Court documents note that he was once a militia leader himself before then working as an informant for the national army.

It is difficult to avoid the suspicion that the deadly trip taken by Catalán and Sharp had been arranged by intelligence and army personnel. And what does the United Nations have to say about it?

In August 2017, five months after the death of the two experts, Secretary-General Guterres presented a 47-page report on the UN investigation into the crime to the Security Council. It was written by Greg Starr, a former top American diplomat.

The report does mention that "rumors" had been circulating in Kasaï that the violence in the region had been "inspired, planned or implemented by the Kabila regime to make it "impossible for voter registration or voting to take place in what is considered an anti-Kabila province.” But it concludes that it was "likely militia members from the Kasai province" who were ultimately responsible for the deaths of Catalán and Sharp.

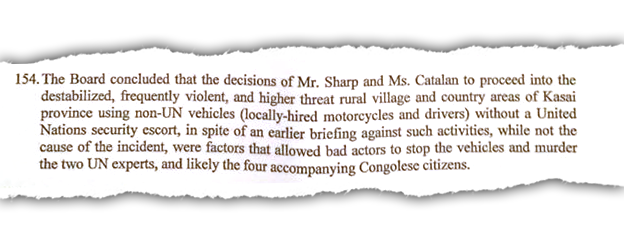

It also lists a large number of criticisms of the expert groups' allegedly overly careless approach. For example, the two had used "non-UN vehicles" on their trip and had not been accompanied by a UN escort, "in spite of an earlier briefing against such activities."

The report states that these decisions, "while not the cause of the incident, were factors that allowed bad actors to stop the vehicles and murder the two UN experts”. The report portrays the two as having been a little too foolhardy and perhaps even naive.

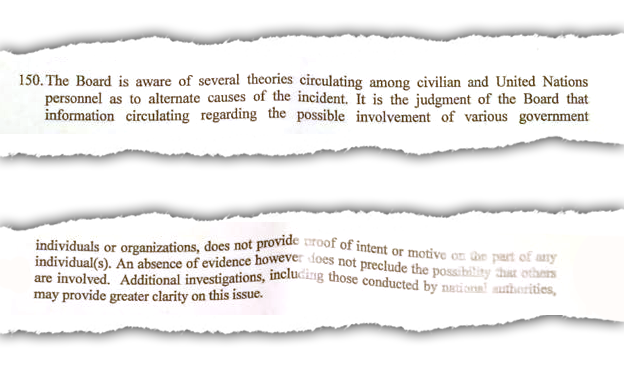

But Starr dedicates little space in his report to indications the government or army might have been involved: “Information circulating regarding the possible involvement of various government individuals or organizations, does not provide proof of intent or motive on the part of any individual(s)."

No evidence of any intentions or motives? The Süddeutsche Zeitung and its international media partners – French international broadcaster RFI, the newspaper Le Monde, Swedish public broadcaster SVT and Foreign Policy magazine – obtained thousands of internal UN documents that the journalists reviewed together. Starr and his team also had access to the same documents when they wrote their report.

They include, for example, reports compiled by investigators with the UN mission in Congo. Only two months after the murders, they began doubting whether the Congolese military judiciary was genuinely interested in finding the truth. They wrote that the investigating prosecutor seemed satisfied with the theory of a single suspect based on the video. But the report's authors also stated that the suspect did not reveal any details “in order to conceal the other aspects of the killing that could involve the government’s hidden influence in this case."

Their analysis speaks of a possible "infiltration of outside elements” in which case, they wrote, government involvement would be likely. They further state that the actions of the Congolese Prosecutor's Office clearly appeared to be “carried out in a single direction in order to charge only a few people and camouflage the the truth about the actual murderers." It continues: "If the situation remains unchanged, the trial will not be fair, and justice has not been done for these two victims and their families.”

Clear words. But Starr ultimately decides to minimize the findings and warnings of his own investigators and take the Congolese authorities out of the line of fire – opting instead to accuse the murdered UN experts of carelessness and lack of respect for security rules.

Why?

In a meeting with Zaida Catalán's mother and sister, he provides that explanation.

Starr has traveled to Öland to meet them for dinner. Elizabeth Morseby has shoved a bag under the table with a recording device inside. A previous phone call with Starr has made her suspicious.

"I do not say army or, you know, things like that because we want the Congolese to continue working with us”, the UN chief investigator tells the two.

Michael Sharp's parents in the U.S. also secretly record their conversation with Starr. During his discussion with them, he confirms: "We do not want to make the report so bad that they cease cooperating on it.” There is, he says, “a line that I do not want to cross."

Thus, as Starr himself admits in these conversations, he has decided to spare the Congolese in his report to ensure that the UN continues to have access to the regime.

And what does he have to say about it today? When reached for comment, Starr says he stands by his report, which, he insists, was only "the written summary of everything" at the time. Time was short, he says, and “we had to get a report there. The report “does not exonerate the DRC government, nor does it say that they were guilty.” Starr also has the UN's support. The international organization says he carried out the investigation "with great professionalism" and did "his very best to inform the families in an open, honest and compassionate manner.”

The UN secretary-general nevertheless commissioned a new investigation into the murder of the two experts. But the Congolese government is apparently continuing to play its game unhindered. A confidential UN report dating from April 18 of this year states that the investigation "continues to be hampered by the continuing interference of the security apparatus."

Maria Morseby still hasn't given up the hope that her daughter's murder will be solved. And despite all the experiences she has thus far had with the organization, she says, "there are personnel within the UN that have been extremely supportive”. Still, the fact that Starr failed to mention the clear indications of links between her daughter's escorts and Congolese intelligence is something she continues to find "totally incomprehensible."

Michael Sharp's mourning parents are also unable to forget how Starr "lied" to them. That he was “blaming the victim”. They have since begun doing the last thing in their power to provide justice to their son: They've begun scattering his ashes in different places around the world. "Next time maybe on the top of Mount Kilimanjaro," says his father John. "Being a citizen of the world, I knew he couldn’t be contained in one place.”